A Theory of Causal Spaces

When we find order in nature, we attribute it to the operation of “laws.”

Newton’s laws determine how objects accelerate. The laws of thermodynamics dictate heat flow. The law of supply and demand governs markets. We observe consistent behavior without ever seeing where a single law comes from or what enforces it.

We assume these laws apply universally. When contradictions appear, we call them paradoxes.

Look closer.

Processes exchange influence, yet each applies its own rules internally. One mass exerts gravitational pull, another responds according to its own properties. A molecule collides with its neighbor and each absorbs energy based on its own state. A buyer offers a price and the seller decides based on their own criteria.

Laws are our interpretations. The processes do the work.

Causal spaces formalize where different rules apply. They let us model how influence propagates within spaces and what happens at their boundaries.

Every paradox arises the same way. Two spaces with different rules get treated as one. Separate the spaces, identify which rules apply where, and the conflict reconciles.

Contents

8.1 Ideal Causal Spaces

8.1.1 Where Causal Spaces Are

8.2 Propagation and Impedance

8.2.1 Causal Propagation

8.2.2 Causal Impedance

8.3 Independent and Interdependent Spaces

8.3.1 Independent Spaces

8.3.2 Interdependent Spaces

8.3.3 Feedback and Bidirectional Induction

8.4 How Every Paradox Works

8.4.1 The Light Duality Paradox

8.4.2 Nimbin’s Paradox

8.4.3 The Liar’s Paradox

8.5 From Causal Spaces to Natural Spaces

8.6 Closing Remarks

8.1 Ideal Causal Spaces

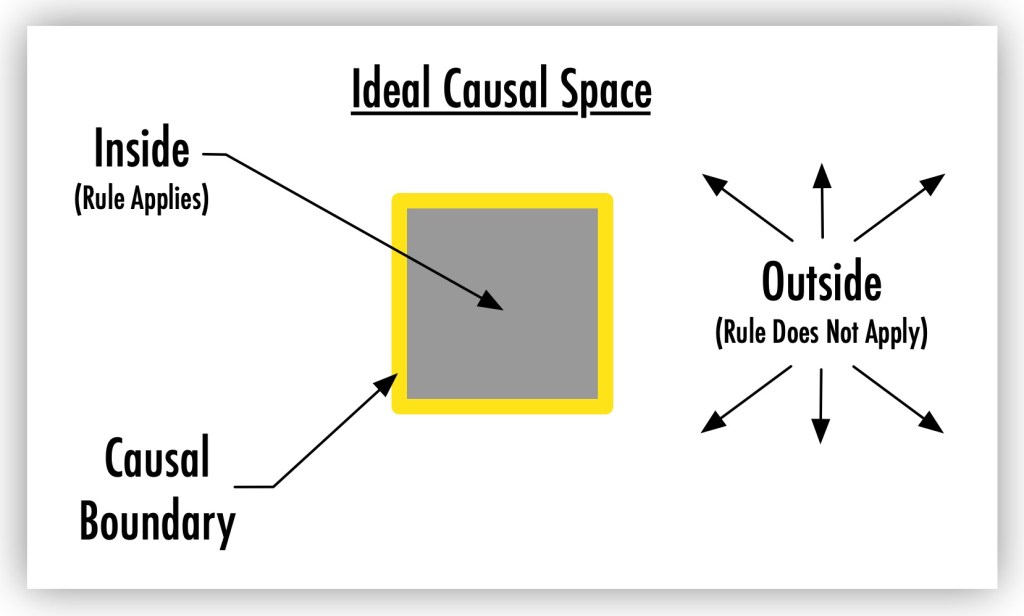

An ideal causal space has well-defined boundaries that determine where its governing rules apply and where they don’t.

Inside this boundary, every process follows the rule completely, while anything outside stays unaffected. The clear separation allows precise analysis: within a given space, causation operates under a single, unbroken principle.

The binary nature of ideal causal spaces makes them useful for studying systems where rules apply without exception. In physics, Newtonian mechanics defines how forces produce acceleration within its range of applicability, while relativistic speeds and quantum scales operate under different principles.

In biology, the nitrogen cycle forms a distinct causal space, governed by fixation, nitrification, and denitrification. Beyond this space, unrelated processes follow entirely different rules. In cognition, logical reasoning exists as its own causal space, where a premise determines its conclusion with certainty (all humans are mortal, Socrates is human, so Socrates is mortal). Outside this space, reasoning follows different principles that don’t adhere to strict deductive logic.

Within an ideal causal space, coherence is absolute: every process inside conforms perfectly to the governing rule, without deviation. Actual systems show more complexity than this rigid model, but ideal causal spaces provide a pure model for understanding causation in its simplest form.

8.1.1 Where Causal Spaces Are

A causal space represents an interpretation of how a process operates in the Causation Domain.

Each process carries its own governing rules internally. The consistency lives in how the process enforces these rules when responding to interaction. An electron exists in the Blue Space, but its causal space, the internal rules that determine its responses, belongs to the electron itself.

Fields work the same way. A field is how we interpret many concurrent, consistent behaviors. If processes consistently pull toward a mass, we call that a gravitational field. The field is our interpretive shorthand for collective causal behavior.

Both the causal space and the field are Red Space interpretations of Blue Space processes. Each gives us a way to map what we can’t directly access.

8.2 Propagation and Impedance

Every process within a causal space follows a defined rule of causation, but the way these processes unfold depends on how they propagate and whether they encounter resistance.

Causal propagation and impedance explain why some processes transition smoothly while others meet resistance or fail to complete.

8.2.1 Causal Propagation

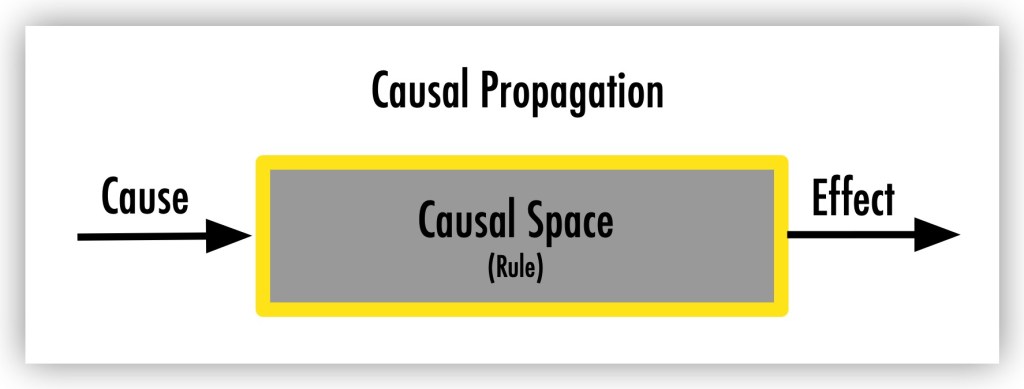

Causal propagation describes how a process moves from one state to another within a causal space.

When a cause state transitions into an effect state, it does so under the enforcement of a rule of causation. Within a defined causal space, this rule applies exclusively to the processes inside: transformations follow its governing principle. The sharper the boundary and the more direct the rule’s application, the more predictable the propagation.

But not all influence propagates with equal ease.

8.2.2 Causal Impedance

Some processes flow freely, adhering closely to the governing rule with little resistance. Others face greater impedance, while some are entirely blocked from transitioning to their expected effect state.

A system with low impedance allows causal rules to apply efficiently, enabling smooth state transitions. A system with high impedance resists change, distorting or preventing the expected outcome.

The relationship can be expressed mathematically:

C = Z × E

Here, the effect state E is influenced by the cause state C, but its transformation is scaled by the impedance Z. When impedance is low, the effect state closely follows from the cause. When impedance is high, movement is slowed or prevented.

Causal impedance plays a critical role across disciplines. In physics, mechanical systems experience impedance as mass, which resists acceleration. In electrical circuits, impedance determines how signals propagate and affects energy transfer. In biology, enzymes lower impedance by making biochemical transformations more efficient, while environmental extremes increase resistance, inhibiting metabolic processes. In social systems, resistance to change acts as impedance, slowing or preventing the adoption of new practices.

Causal impedance explains why transformations sometimes lead nowhere or take unexpected paths.

8.3 Independent and Interdependent Spaces

Every causal space operates according to its own rule, but how these spaces relate determines the complexity of the systems they form. Some spaces stay entirely self-contained, functioning independently. Others interact dynamically, influencing and responding to one another in ways that direct the processes flowing through them.

Note to the Reader: “red space” and “blue space” now represent any causal spaces, not just interpretation and causation. Their meaning depends on context.

8.3.1 Independent Spaces

Independent causal spaces function autonomously, governed exclusively by their own rules. Processes within these spaces transition from cause states to effect states without external influence. Each transformation occurs solely according to the internal rule of causation, without interaction from other spaces.

Two causal spaces, blue and red:

Within the blue space, processes develop according to its specific rules, moving from a cause state (Cblue) to an effect state (Eblue) without interference from outside factors. The same holds for the red space, where processes transition from Cred to Ered, following a distinct set of governing principles.

These spaces operate independently. Processes within the blue space follow their own rules while the red space operates according to its distinct governing principles. The separation allows analysis of each system in isolation, keeping interactions within a given space predictable and internally consistent.

8.3.2 Interdependent Spaces

Many systems feature interdependent causal spaces where changes in one context induce transformations in another. While independent spaces function autonomously, interdependent spaces are dynamically linked, allowing processes to influence and respond to one another across contexts.

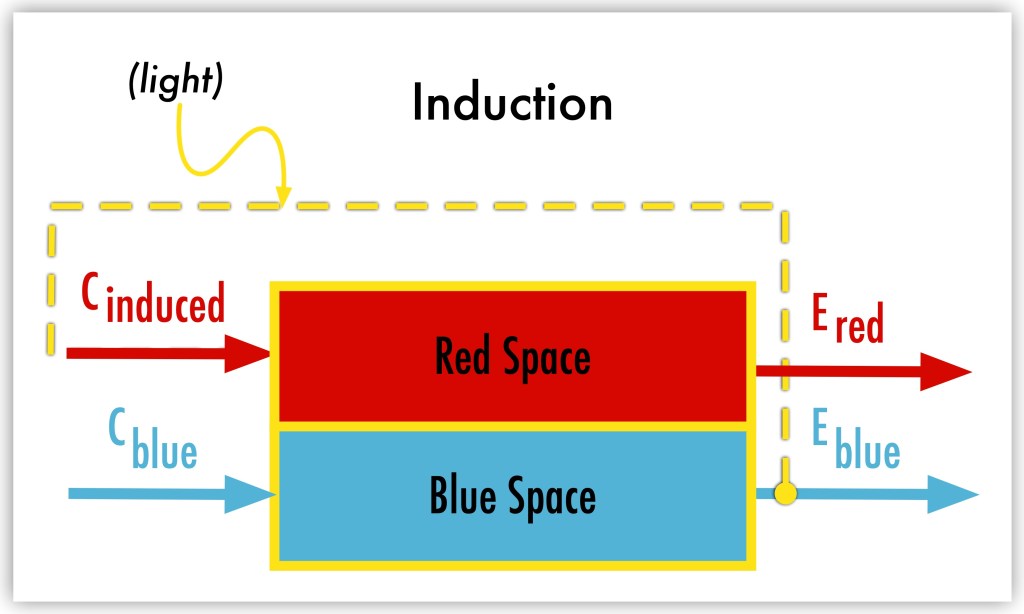

The blue space and red space interact:

Through causal induction, an effect in one space induces a cause in another, creating an orthogonal induction path between the spaces.

Since each space follows its own governing rules, the induced cause arises according to the enforcement of the internal rules of the receiving process, propagating within an orthogonal causal space.

8.3.3 Feedback and Bidirectional Induction

The diagram below illustrates how an effect (Eblue) in the blue space produces an induced cause (Cinduced) in the red space, which then follows its own rule to generate an effect (Ered).

Induction is often bidirectional, meaning that just as the blue space influences the red space, the red space can also direct processes in the blue space. This feedback loop creates a continuous exchange, where both spaces dynamically adjust in response to one another.

The interdependence appears everywhere. In taste and nutrition, sensory perception and metabolic processing form interdependent spaces. The perception of sweetness in the sensory space triggers insulin release in the nutritional space, altering how the body processes sugar. Biochemical needs also influence sensory perception; a sodium deficiency can induce a craving for salty foods.

A similar interdependence exists between sense perception and motion control, where vision and motor function influence each other through bidirectional causation. Visual information about an object’s position induces motion adjustments in the motor space, while motor feedback refines sensory perception, improving balance and coordination. Movement actively transforms how perception functions while perception guides motor responses.

The bidirectional dynamic explains what Gibson called affordances: the opportunities for action that an environment provides to a process. Affordances arise when a process can both construct meaning from environmental signals and project effects back into that environment. Both directions require compatible impedance.

A musician experiences affordances in instruments that others can’t because their internal rules have developed matched impedance between auditory processing and motor responses. The environment provides the signals, but affordances only open up when the process can engage bidirectionally through impedance compatibility in both directions.

In economics and individual perception, large-scale economic changes impact personal decision-making. A rise in inflation induces a perception of decreased purchasing power within the psychological space, leading individuals to adjust their behavior by spending less. This shift in consumer behavior then feeds back into the economic space, influencing broader market trends.

Knowing when causal spaces are independent and when they interact is critical for understanding how processes develop across multiple contexts.

8.4 How Every Paradox Works

Paradoxes expose where our models of causation are misapplied or misunderstood. They arise when we impose the wrong rules in the wrong place, treating separate domains as if they operate under a single framework. Recognizing these boundaries is key to resolving contradictions.

Cross-domain interactions create apparent contradictions when incompatible rules collide. Applying the correct framework dissolves these inconsistencies.

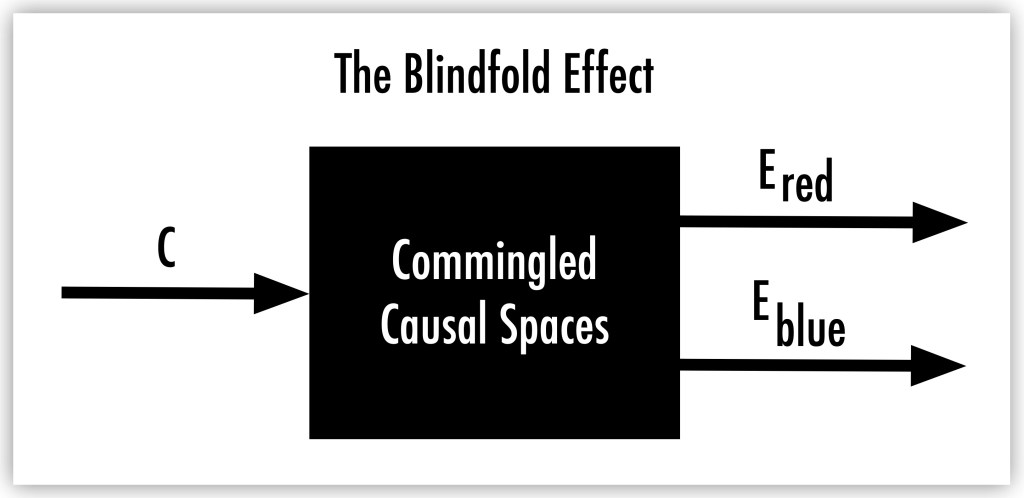

In Figure 30, E_blue and E_red both appear to originate from the same cause C:

The black box labeled “Commingled Causal Spaces” represents the absence of differentiation in the mind, leading to effects that can’t be reconciled within a single logical framework. When E_blue and E_red contradict each other under a unified interpretation, the result is a paradox.

Separating these environments and identifying their rules and boundaries clarifies the relationships between cause and effect. The confusion introduced by the Blindfold Effect disappears, and what initially appears as a paradox turns into an opportunity to refine our understanding.

Three paradoxes demonstrate this.

The Liar’s Paradox exists as an actual statement that creates genuine logical problems. Light genuinely exhibits both wave and particle behaviors. Nimbin’s experience of contradictory food responses is authentic.

Traditional approaches treat these as puzzles to solve within a single framework. Natural Reality recognizes them as evidence that reality operates across multiple domains with distinct principles. The paradoxes reveal features of reality that refuses to be contained within any single causal framework.

How do we identify causal spaces? We model them and test until the model works. When contradictions surface, we examine where incompatible rules might apply. We draw boundaries, test predictions, adjust when results don’t match. The process is iterative: model, test, refine.

The model works when the paradox disappears. The resolution might feel counterintuitive to our native assumptions, but that discomfort reveals exactly which assumptions we’ve been making unconsciously. When wave-particle duality stops being contradictory because we recognize measurement and propagation as distinct domains, we’ve exposed our hidden assumption that all properties must exist uniformly. When the Liar’s sentence resolves through separating creation from evaluation, we’ve discovered our unexamined belief that language and logic operate under identical rules. These contradictions serve as diagnostic tools, showing us the boundaries of our unconscious frameworks.

A causal space is validated by whether it helps us predict and work with what happens.

8.4.1 Light Duality Paradox

The paradox of light behaving as both a wave and a particle arises from the interaction between quantum phenomena and the physical world. In the blue context of quantum mechanics, light propagates as an electromagnetic wave, displaying interference patterns when unmeasured. The blue effect (E_blue) is this wave-like behavior.

Light also interacts with the red domain of physical measurement, where observation introduces constraints. When light passes through a slit or strikes a detector, the measuring system engages with light’s propagation in a way that produces discrete, localized results. This interaction creates an induced cause in the measurement domain, where the detection apparatus can only respond in quantized ways. This produces the red effect (E_red): the detection of light as individual photons. The change occurs not in light itself but in how the measurement process engages with continuous electromagnetic propagation.

The paradox arises because these two effects follow different rules. Wave interference requires continuous field behavior, while particle detection produces localized, discrete events. Recognizing that light operates across distinct domains resolves the paradox. Whether light appears as wave or particle depends on which domain governs the interaction: continuous propagation in the Blue Space, or discrete measurement in the interpretive apparatus.

8.4.2 Nimbin’s Paradox

Nimbin’s conflicting relationship with food, his love for sugary treats and dislike of vegetables, illustrates a paradox arising from misaligned domains. In the blue domain of nutrition, sugar consumption leads to long-term health consequences. The blue effect (E_blue) is the accumulation of these negative outcomes.

Yet in the red domain of sensory perception, sugar interacts with taste receptors, producing an immediate positive experience. This creates an induced cause, leading to an effect that contradicts the blue domain: the red effect (E_red) is the enjoyment of sugary foods.

The paradox arises because Nimbin instinctively associates the pleasure of sweetness with a positive outcome, without recognizing that the nutritional consequences happen in a separate domain. To resolve this paradox, Nimbin learns to differentiate between the sensory space of immediate experience and the metabolic space of long-term effects, allowing him to see that a single substance can produce contradictory results depending on where it’s processed.

8.4.3 The Liar’s Paradox

Consider the statement “This sentence is false.” Most explanations attribute the paradox to self-reference, but that misses what actually creates the problem. Self-reference operates under one set of rules while truth evaluation operates under another.

In the blue domain of writing, grammatical rules permit self-reference without constraint. The sentence structure is valid. In the red domain of logical evaluation, truth assessment requires determinate values. When the reader attempts to evaluate a self-referential statement’s truth value, they enter an endless loop: if the sentence is true, it must be false; if false, it must be true. The paradox arises because grammatical rules permit what logical evaluation cannot resolve. You create using one domain’s rules, then evaluate using incompatible rules from another domain.

The paradox has puzzled logicians for millennia because from within the logical domain alone, it appears unsolvable. The resolution comes from recognizing that the sentence’s creation and its evaluation operate in distinct domains. Meaning operates within specific environments governed by different rules, just as causation does. What seems paradoxical signals that constraints from one context are being applied to another.

Causal spaces show how paradoxes form and resolve. They serve as insights that extend our understanding of causality. Recognizing the presence of multiple governing environments helps us move beyond contradictions and observe how systems interact, develop, and generate complexity. The capacity to differentiate and model causation across these boundaries is central to understanding both paradoxes and the broader dynamics of Natural Reality.

8.5 From Causal Spaces to Natural Spaces

A causal space is a concept we use to describe causality. Causal spaces help us understand how transformations occur, defining a space through rules of causation.

How do these spaces turn into Natural Spaces, environments where causation happens as we experience it in nature?

Through richness of interaction.

A Natural Space is an interpretative space that includes additional layers of characterization, making it recognizable as part of a physical, biological, chemical, cosmological, or other universal system. While a causal space is defined purely by its governing rules, a Natural Space is one where these rules take on meaning through their presence in nature itself.

Natural Spaces are characterized by:

- Persistence: They sustain themselves.

- Self-adjustment: They exhibit feedback and stabilization mechanisms.

- Emergence: They generate complex behaviors from simple interactions.

The atomic space, the chemical space, the cosmological space are Natural Spaces. These support a vast range of interactions, processes, and variability, allowing them to behave in ways we recognize as nature.

When we place a system inside a confined environment, we’re approximating a Natural Space rather than creating one. The difference lies in the scale and diversity of interactions. A Natural Space must be expansive in the variety of its processes, allowing for Incoherence, self-regulation, and complexity that drive behavior.

Every Natural Space is a causal space. A causal space only turns into a Natural Space when it exhibits the breadth of interactions necessary for emergence.

8.6 Closing Remarks

Causation follows different rules in different causal spaces. Quantum interactions, biological processes, and mechanical systems each operate according to distinct governing principles that determine how processes transform and influence one another.

Causal spaces are environments defined by their governing principles rather than location or time. By recognizing these boundaries, we resolve paradoxes that have persisted for centuries. Wave-particle duality, the Liar’s Paradox, even everyday dissonance between people all arise from misapplying the rules of one space to another.

The framework gives us tools for mapping how influence actually propagates. We can identify which processes enforce which rules, track smooth flow within spaces, and measure resistance when influence crosses boundaries. The same mathematics model propagation whether examining internal dynamics or cross-space coupling.

Understanding these boundaries transforms how we work with change. We recognize when different logics operate in parallel. We see where resistance emerges and where processes align. Contradictions become diagnostic tools showing us exactly where incompatible rules meet.

When processes cross between different rule systems, new dynamics arise. Chapter 9 explores those dynamics and the formal tools for modeling them.