Causal Dynamics

We now attempt to model the operation of a domain that otherwise goes unseen.

Impedance measures resistance. Admittance measures ease of flow. Phase alignment measures synchronization between different rules. Complex numbers capture the orthogonal relationship between Causation and Interpretation.

These quantities are calculable. The same math applies across learning, ecosystems, technology adoption, and economic change.

The framework quantifies Incoherence. When processes change their impedance relationships, we measure that change as ΔZ. Emergence has a calculable threshold.

Contents

9.1 Processes and Causal Spaces

9.1.1 How Processes Work

9.1.2 Impedance and Admittance

9.1.3 Causal Propagation

9.1.4 Feedforward

9.1.5 Feedback

9.1.6 Multiple Causal Spaces

9.1.7 Causal Modeling

9.1.8 Cross-Impedance and Cross-Admittance

9.1.9 Asymmetric Cross-Impedance and Admittance

9.1.10 Orthogonality of Induction Paths

9.1.11 Blue-to-Red and Red-to-Blue Induction

9.1.12 Phase Alignment

9.1.13 Asymmetric Phase Alignment

9.1.14 Synthesis

9.2 Resonance

9.2.1 General Resonance

9.2.2 Feedback Resonance

9.2.3 Feedforward Resonance

9.2.4 Damped Resonance

9.2.5 Forced Resonance

9.2.6 Phase-Shifting Resonance

9.2.7 Nonlinear Resonance

9.2.8 Stochastic Resonance

9.2.9 Multi-Space Resonance

9.2.10 Practical Applications of Resonance

9.2.11 Synthesis

9.3 Incoherence

9.3.1 Coherent Interactions

9.3.2 What is Incoherence?

9.3.3 The Causation Axis

9.3.4 Incoherence as Decay-Agnostic

9.3.5 Quantifying Incoherence

9.3.6 Applications of Incoherence

9.3.7 Synthesis

9.4 Emergence and Harmonization

9.4.1 The Concept of Emergence

9.4.2 Fueled by Incoherence

9.4.3 Harmonization

9.5 Theoretical Case Studies

9.5.1 Explanation of Values

9.5.2 Case Study 1: Short-Term vs. Long-Term

9.5.3 Case Study 2: Exercise vs. Nutrition

9.5.4 Case Study 3: Market and Consumer

9.5.5 Proposed Case Studies and Empirical Validation

9.5.6 Synthesis

9.6 Closing Remarks

9.1 Processes and Causal Spaces

Causal interactions follow defined paths, encountering resistance, alignment, or redirection as they move through different spaces. Impedance, admittance, and cross-impedance describe how influence flows, accumulates, and interacts across causal spaces.

Processes operate within causal spaces according to their governing rules. Influence propagates smoothly through some spaces, while others create resistance that changes its course.

Causal propagation occurs in feedforward and feedback loops. Feedforward pushes influence in one direction. Feedback regulates recursively. Influence can cross between causal spaces, producing behaviors that no single space would generate alone.

These dynamics underlie resonance, Incoherence, and emergence.

9.1.1 How Processes Work

A process transforms a cause state into an effect state. This transformation follows the governing rules of a causal space. Influence can propagate in parallel, interact recursively, or respond to changing conditions.

Cause and effect are states. A cause state initiates an interaction, and an effect state follows. An effect can turn into a new cause, driving further interactions.

Propagation can be continuous, discrete, or event-driven, depending on the causal space.

9.1.2 Impedance and Admittance

Impedance measures the resistance a process encounters when propagating through a causal space, reflecting how well the process aligns with the governing rules of that space.

Higher impedance means the process is poorly aligned with these rules, making it harder for the cause to produce an effect. Lower impedance means smoother transitions, where causes propagate more easily.

Admittance is the inverse of impedance: how easily a cause state generates an effect. Processes with higher impedance have lower admittance, meaning they face significant resistance, while high admittance reflects minimal resistance and efficient cause-effect transitions.

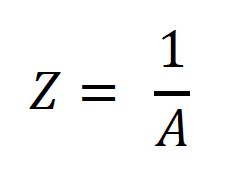

Mathematically, impedance Z and admittance A are related as follows:

Where Z is the impedance of the process and A is the admittance of the process. Admittance can be normalized to a reference process, giving us a way to compare how efficiently processes operate within a causal space.

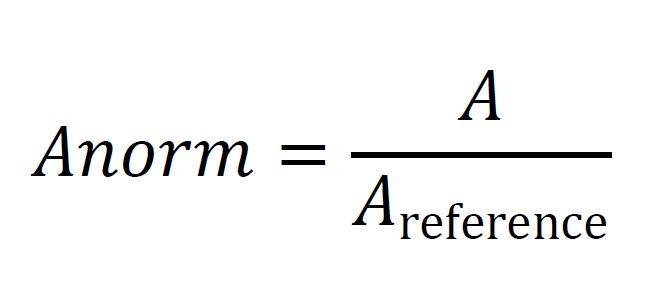

The normalized admittance is expressed as:

Where is the admittance of an ideal or baseline process, typically normalized to 1. Light, which represents ideal causal flow with minimal impedance, often serves as a reference process in physical systems.

Intuition for Impedance and Admittance: In biological systems, impedance represents the difficulty a biochemical signal faces when propagating through a highly regulated pathway. A hormone signal encountering a complex regulatory network faces high impedance, leading to delays or weakened response. A more direct, less regulated pathway has low impedance, allowing fast and efficient signaling.

In economic systems, impedance represents the friction that prevents rapid adaptation to market changes, such as heavy regulations that slow response to changes in supply or demand. Markets with low impedance adapt more fluidly to changes, exhibiting high admittance.

Every process has a natural impedance, which consists of both a causal component (real) and an interpretative component (imaginary). The causal component represents direct resistance to propagation, while the interpretative component accounts for induced effects that emerge through cross-space interactions.

Here, we focus only on the real component and refer to it as causal impedance for clarity. While impedance can be modeled as a complex parameter, including both direct and induced resistance, this chapter focuses on the direct resistance that affects causal propagation within a single space, isolating the mechanics of causality before reintroducing interpretative effects later.

9.1.3 Causal Propagation

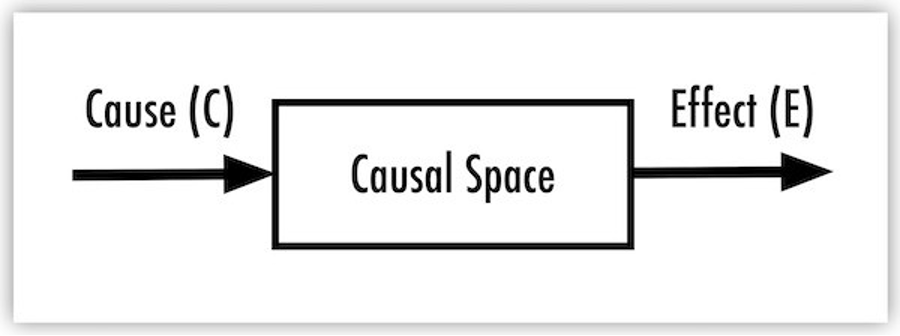

Causal propagation describes the transformation of cause states into effect states as they pass through a causal space, governed by one or more internal rules.

In the diagram, cause (C) enters the causal space, where it is processed according to the space’s rules, resulting in an effect (E):

Propagation can happen in two main ways: feedforward and feedback.

9.1.4 Feedforward

Feedforward Propagation occurs when the cause directly leads to an effect without looping back. This is the most basic form of propagation, where the system moves linearly from one interaction to the next.

The relationship between cause and effect during feedforward propagation is described by the equation:

Where:

- E is the effect state,

- C is the cause state,

- A is the admittance of the process.

Higher admittance leads to more efficient propagation of causes into effects, creating smoother transitions.

Intuition for Feedforward Propagation: This concept mirrors Newton’s second law of motion, where force F is analogous to the cause state C, mass m to impedance, and acceleration a to the effect E. A higher mass (impedance) reduces the resulting acceleration (effect) for a given applied force (cause), just as higher impedance in a causal space diminishes the ability of a cause to generate a strong effect.

9.1.5 Feedback

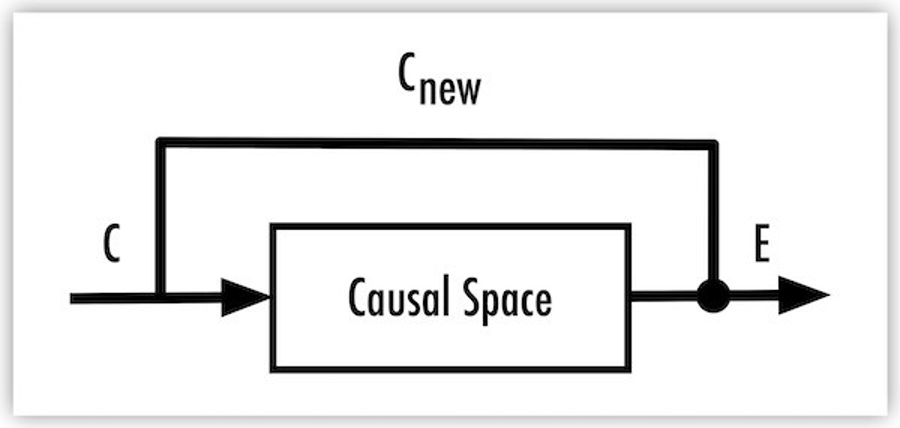

Feedback Propagation introduces a recursive interaction, where the effect loops back to become the cause of subsequent interactions. It allows for oscillations, self-correction, and iterative development, enabling systems to adjust based on prior outcomes.

The relationship between the previous effect and the new cause in feedback propagation is described as:

Where:

- Cnew is the new cause state,

- Eprevious is the previous effect state,

- F is the feedback factor.

Feedback allows for oscillations, self-correction, and iterative development, enabling systems to adjust based on prior outcomes.

Intuition for Feedback Propagation: Consider a thermostat regulating the temperature in a heating system. When the temperature (effect) reaches a set threshold, the thermostat sends a signal (cause) to turn the heating system on or off, creating a feedback loop. This self-regulating mechanism is a common example of feedback. In biological systems, feedback occurs in neural networks, where neuron firings adjust future firings based on previous responses, introducing adaptation and control mechanisms.

9.1.6 Multiple Causal Spaces

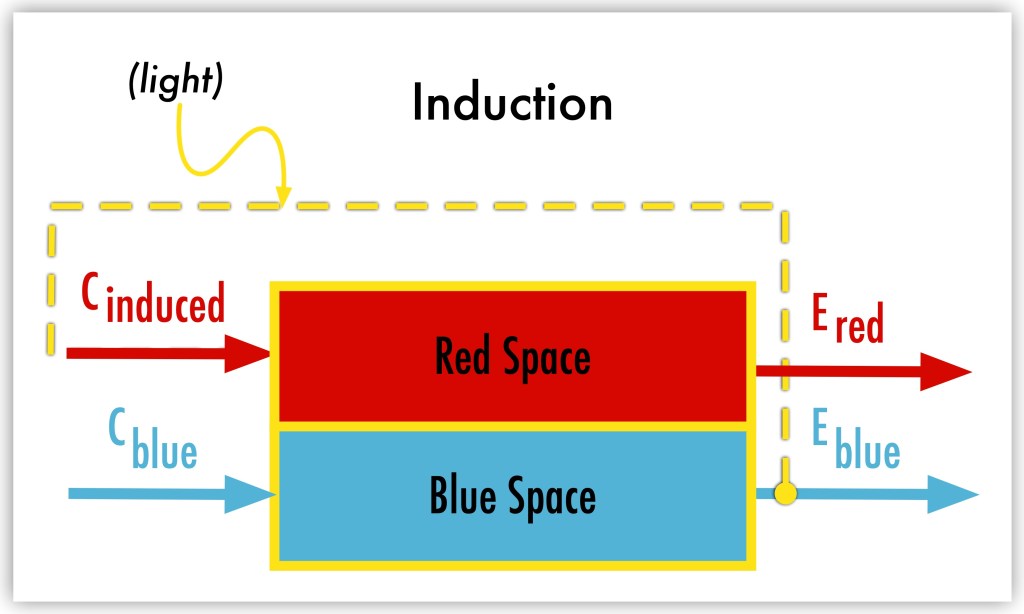

Processes can propagate across multiple causal spaces, each defined by its own governing rules. These spaces represent distinct environments where different principles apply. Induction couples these spaces, carrying influence across contexts. Within each space, processes interact according to its rules, whether internally or with other processes.

For ease of explanation, we focus on two causal spaces, one labeled blue and another red. Each operates under distinct governing rules, and the coupling of spaces occurs through the interaction of processes rather than through the spaces themselves interacting directly.

Intuition for Multiple Causal Spaces: Consider a scenario in which blue space represents social behavior and red space represents economic behavior. A social movement advocating for environmental practices (blue space) can influence consumer demand for sustainable products (red space). These spaces are coupled through the interaction of the processes within them: social actions (processes in blue space) interact with economic factors (processes in red space), but each space follows its own governing rules.

9.1.7 Causal Modeling

The interactions across causal spaces are understood through causal modeling. Causal models formalize how processes interact within a space, and how processes in different spaces influence one another through coupling. While the spaces themselves stay distinct, the processes that operate within them allow for dynamic interactions and emergent behaviors.

We use a two-space model (blue space and red space) to illustrate fundamental principles without unnecessary complexity. While we focus on two spaces, the same principles apply to systems with multiple spaces, each governed by its own causal rules and coupled through interacting processes.

Intuition for Causal Modeling: In biological systems, cognitive processes (blue space) and neural signaling (red space) interact. Cognitive decisions or emotional states can trigger physiological responses (e.g., stress hormones), which in turn feed back into cognition by altering mood, decision-making, or perception. These processes are coupled but follow the distinct governing rules of their respective spaces.

9.1.8 Cross-Impedance and Cross-Admittance

Cross-impedance quantifies the resistance encountered when a process transitions between causal spaces.

It reflects the degree of misalignment between the rules enforced in each space. The greater the misalignment, the higher the cross-impedance, leading to increased resistance in causal propagation.

Cross-impedance can be asymmetric, meaning the resistance in one direction (e.g., from blue to red space) can be higher than in the reverse direction (from red to blue space).

Cross-admittance is the inverse of cross-impedance: how easily processes propagate between causal spaces. When cross-admittance is high, processes flow smoothly across the boundary between spaces, leading to efficient cause-effect transitions. High cross-impedance creates resistance, hindering the flow of causes and effects across spaces.

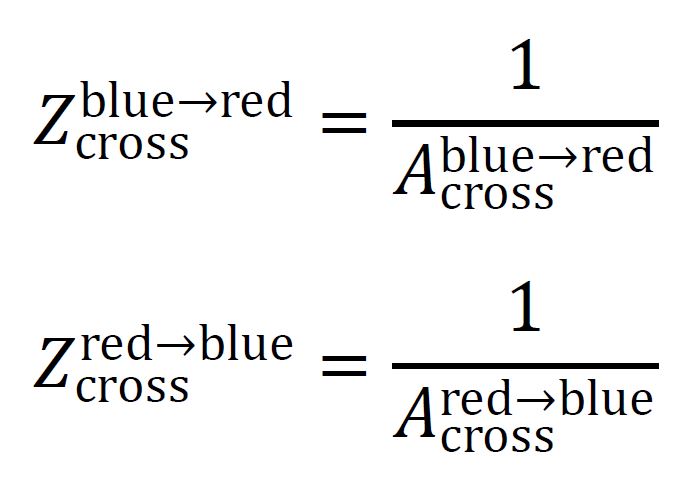

Mathematically, the relationship between cross-impedance and cross-admittance is expressed as:

Where:

- Zcross is the cross-impedance between two causal spaces,

- Across is the cross-admittance, representing the ease of propagation between spaces.

Intuition for Cross-Impedance and Cross-Admittance: In a biological context, cross-impedance represents the difficulty a process optimized for one cellular environment (blue space) faces when it attempts to function in a different cellular environment (red space) with incompatible conditions. A drug designed to target a specific organ can encounter high cross-impedance when it interacts with other organs that don’t support its intended function.

Many real-world systems exhibit asymmetric cross-impedance, where the resistance to causal propagation differs depending on the direction of interaction between causal spaces. The transition from blue to red space can encounter greater or lesser resistance than the transition from red to blue space, creating directional dependencies in how causes and effects propagate. We often assume symmetric cross-impedance to simplify discussions of resonance and emergence, but recognizing asymmetry is essential for accurately modeling complex systems.

When one causal space has a stronger influence over another, such as in mind-body interactions or hierarchical organizational systems, directional dependencies affect interactions in meaningful ways.

9.1.9 Asymmetric Cross-Impedance and Admittance

Asymmetric cross-impedance occurs when the interaction between two causal spaces is unbalanced. A strong blue-space cause can induce a relatively weak red space effect, while the opposite (a red space cause inducing a blue space effect) can encounter less resistance. This directional asymmetry is important in systems where one causal space dominates another in terms of influence or control.

The relationship between cross-impedance and cross-admittance remains similar to the symmetric case:

Where:

- Zblue→red, cross is the impedance from blue to red space.

- Ablue→red, cross is the admittance from blue to red space.

- Zred→blue, cross is the impedance from red to blue space.

- Ared→blue, cross is the admittance from red to blue space.

This asymmetry reflects how the rules governing one space (e.g., cognitive processes in a red space) can more easily induce effects in another space (e.g., physiological responses in the blue space), while the reverse interaction can face greater impedance.

Practical Example: In the mind-body interaction, asymmetric cross-impedance is evident. A mental decision or thought process (red space) can trigger a physiological response (blue space) with relatively low impedance, such as raising your heart rate through stress or anticipation. Physiological conditions like fatigue (blue space) can face much higher resistance in influencing your mental state (red space), as the body’s signals struggle to induce a corresponding cognitive effect. This asymmetry illustrates how different causal spaces interact with varying levels of influence.

Intuition for Asymmetric Cross-Impedance: Imagine trying to push a door that swings more easily one way than the other. Pushing the door in one direction (blue to red space) could be easy because the hinges are well-oiled in that direction, representing low impedance. Trying to pull the door back in the opposite direction (red to blue space) could be difficult because of rusted hinges or resistance, symbolizing higher impedance. This imbalance in how easily you can open or close the door reflects the concept of asymmetric cross-impedance in causal dynamics.

9.1.10 Orthogonality of Induction Paths

Induction paths between causal spaces (such as blue and red spaces) are orthogonal to the direct causal paths governed by the rules within each space. This orthogonality represents the distinction between interactions that stay within a single causal space and those that cross between spaces.

The direct causal path operates strictly according to the rules of a specific causal space. In the blue space, causes (Cblue) and effects (Eblue) are governed by blue space dynamics, like mechanical or physical laws. When an effect in the blue space induces a cause (Cinduced) in the red space, the induction follows a different set of rules. The red space operates by its own governing principles, creating an interpretive change distinct from the blue space rules. The induction path links the blue space and the red space, with distinct effects in each space.

An impedance framework represents the orthogonality, where the interaction across spaces depends on how much impedance exists between them.

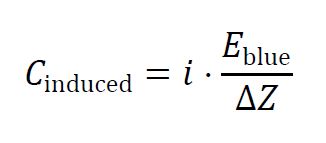

The induction path is modeled as:

Where:

- Cinduced represents the induced cause in the red space,

- i is the imaginary unit, representing the orthogonal relationship between the blue and red spaces,

- Eblue is the effect in the blue space,

- ΔZ represents the impedance difference between the blue and red spaces.

The formalism shows how the interaction between effects and causes changes as they cross causal boundaries. The interpretive dynamics of each space (like blue space’s physical rules versus red space’s abstract rules) lead to different outcomes depending on the relative causal impedance. As the impedance difference increases, the ease with which causes propagate across spaces decreases, resulting in greater difficulty in inducing effects across boundaries.

By later introducing Incoherence, ΔZ serves as the impedance difference that determines how smoothly or chaotically these interactions occur, forming a consistent model that applies both in simpler cross-space interactions and more complex emergent behavior in later sections.

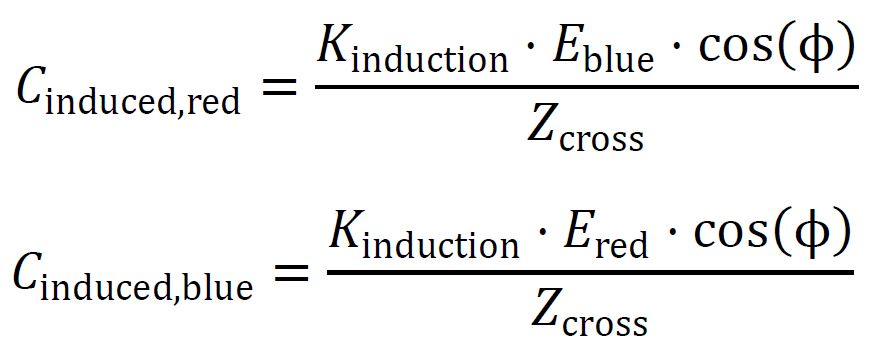

9.1.11 Blue-to-Red and Red-to-Blue Induction

The interaction between spaces is not limited to one direction. Induction can occur from blue to red or from red to blue, depending on the dynamic interaction between the causal spaces. The equations modeling this two-way induction path are as follows:

Where:

- Cinduced, red represents the cause induced in the red space from the blue space’s effect.

- Cinduced, blue represents the cause induced in the blue space from the red space’s effect.

- Kinduction is the induction coefficient that measures how effectively causes propagate between spaces.

- cos(𝜙) measures phase alignment between the two spaces, influencing how smoothly causes are induced.

- Zcross is the cross-impedance presented by processes traversing the spaces.

Intuition for Orthogonality of Induction Paths: Imagine the interaction between human cognition (blue space) and neural activity (red space). A cognitive decision or thought arises in the mind (blue space), inducing a physiological response in the brain (red space). The rules governing the psychological decision (blue space) differ from those governing neural responses (red space). This orthogonality captures the fact that neither system’s rules can fully explain the interaction on their own. The induced response in the red space develops according to its own governing principles.

In artificial intelligence, orthogonality can describe how one algorithm processes data (blue space), which then induces actions in another, more specialized algorithm (red space). The induction process between models follows the induction path, transforming data interpretation based on the rules of each model, yielding different behaviors and outcomes.

9.1.12 Phase Alignment

Phase alignment describes the degree of synchronization between the governing rules of two causal spaces. When two spaces are in phase, their rules align, minimizing impedance and allowing for smoother transitions of cause states. When spaces are out of phase, even minor misalignments in their rules can significantly increase impedance and hinder causal propagation.

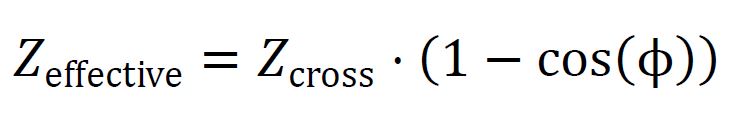

Mathematically, phase alignment is represented by the phase difference (ϕ) between two spaces:

Where:

- Zeffective is the effective cross-impedance accounting for phase alignment,

- Zcross is the base cross-impedance,

- ϕ is the phase difference between the governing rules of the spaces.

When the phase difference ϕ = 0, the spaces are perfectly aligned, and cross-impedance is minimized. As the phase difference increases, cross-impedance also increases, reducing the efficiency of causal propagation. When ϕ = π, the spaces are completely out of phase, maximizing cross-impedance and preventing causal flow between the spaces.

Intuition for Phase Alignment: This concept mirrors phase alignment in oscillating systems like electrical circuits. When two circuits are in phase, their oscillations reinforce each other, leading to constructive interference. When out of phase, they interfere destructively. Two causal spaces in phase harmonize, enabling efficient propagation of causes. A social system (blue space) and a political system (red space) can align when public opinion (blue space) and policy changes (red space) are synchronized, allowing for smoother implementation of new policies. When they are out of phase, such as when public opinion changes rapidly but policy lags, resistance increases, delaying the interaction between the spaces.

9.1.13 Asymmetric Phase Alignment:

The alignment between two causal spaces can be asymmetrical. The degree to which a cause in the blue space induces an effect in the red space can differ from how a cause in the red space induces an effect in the blue space. This asymmetry arises from differences in the rules that govern each space and the nature of the causal interaction.

We represent this asymmetry as follows:

Where:

- Φblue→red is the phase alignment from blue to red space.

- Φred→blue is the phase alignment from red to blue space.

- ϕblue→red and ϕred→blue represent the phase differences in each direction.

In asymmetric systems, the phase alignment differs depending on whether the cause is propagating from the blue space to the red space or vice versa. This variation impacts the efficiency of causal interactions, leading to different outcomes based on directionality.

The formulation models asymmetry in cross-space interactions, showing that alignment between spaces varies based on the direction of causal flow. Tuning the phase alignment in each direction optimizes the propagation of causes and effects between the spaces.

Asymmetry in cross-space interactions plays a critical role in systems where one space can have a stronger influence over the other, leading to hierarchical dynamics and control mechanisms. The implications of these asymmetries are explored further in the analysis of Incoherence and resonance.

Intuition for Asymmetric Phase Alignment: Imagine the interaction between a lead violinist (blue space) and a conductor (red space). The conductor’s direction (cause in red space) influences the violinist’s playing (effect in blue space) with high effectiveness and synchronization (low phase difference). The influence of the violinist’s playing on the conductor’s decisions (from blue to red space) can be weaker or more delayed (higher phase difference), illustrating asymmetry in the interaction. This example shows how influence can vary between spaces, with red space exerting more direct control over blue space.

Real-world systems often exhibit asymmetry in both phase alignment and cross-impedance. The model incorporates asymmetry where necessary, depending on the nature of the system being studied.

We can modify the harmonic resonance equations to account for directional differences in phase alignment, leading to a richer understanding of how complex systems behave when there is asymmetry in both phase and impedance.

9.1.14 Synthesis

Influence propagates through multiple causal spaces, each with distinct rules. Impedance and admittance quantify the resistance and ease with which causes generate effects, while cross-impedance and cross-admittance extend this understanding to processes moving across distinct causal spaces.

Phase alignment determines synchronization between spaces. When in phase, systems operate with minimal resistance, creating smoother causal transitions. When causal spaces are out of phase, cross-impedance increases, hindering interactions and creating friction in dynamic systems.

Orthogonality shows how interactions between spaces introduce a change in causal dynamics, as processes adapt to new governing rules. Orthogonality is critical for understanding how different contexts, whether cognitive, economic, biological, or social, interact and influence each other.

Resonance amplifies cause-effect interactions across causal spaces. When spaces align, resonance amplifies their interactions, producing emergent behaviors greater than the sum of their individual parts.

9.2 Resonance

In Natural Reality, resonance occurs when interacting processes synchronize, enhancing their cause-effect transitions. This alignment of impedance and admittance allows cause states to propagate more efficiently, amplifying their effects.

The orthogonality of induction paths between causal spaces is captured using complex numbers, where induced causes in one space are orthogonal to the direct causal path in another. This introduces real and imaginary components to the interactions, reflecting how cross-space dynamics generate effects through the application of different rules.

9.2.1 General Resonance

The general resonance equation is:

Where:

- R represents resonance,

- Across is the cross-admittance of the processes,

- Zcross is the cross-impedance of the processes,

- Δθ is the phase difference between the governing rules of the processes across spaces.

The imaginary term captures the orthogonality of the induction path, showing how interactions shift between real (direct) and imaginary (induced) components. Induction between spaces produces new causal effects, each governed by the distinct rules of its respective causal space.

Intuition for General Resonance: Resonance can be understood by comparing it to systems like electrical circuits or oscillating mechanical systems. When two oscillators are in phase, their oscillations reinforce each other, similar to how resonance in Natural Reality amplifies cause-effect interactions when processes are aligned. The imaginary component models the interaction that occurs when the causal spaces are not perfectly aligned, introducing a change in interpretation as the cause crosses spaces, like how out-of-phase oscillators interfere with each other.

9.2.2 Feedback Resonance

Resonance frequently arises from feedback loops, where cause and effect states oscillate within a single causal space. These oscillations occur when cause states cyclically influence subsequent effect states, leading to periodic interactions that reinforce each other and amplify the system’s behavior when aligned.

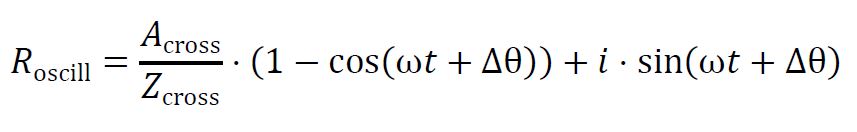

The oscillation-driven resonance formula is:

Where:

- Roscill accounts for the frequency of oscillations in the system,

- Across is the cross-admittance between the interacting processes,

- Zcross is the cross-impedance,

- Δθ is the phase difference between interacting processes.

Intuition for Feedback Resonance: Think of a compressed spring that, when released, oscillates back and forth. The initial force (cause) is transformed into motion (effect), and that effect, in turn, feeds back into the system as the next cause, leading to oscillations. In Natural Reality, similar feedback loops allow oscillations to grow if the phases align, amplifying effects.

9.2.3 Feedforward Resonance

In feedforward resonance, the effect in one space induces a cause in another space, creating a directional flow of influence. When these induced interactions are oscillatory, the resonance between spaces can drive amplification, where oscillations in one space trigger oscillations in another.

The resonance equation for feedforward-driven oscillations is:

Intuition for Feedforward Resonance: Feedforward resonance is like a relay race. The cause in one space passes on the baton (its effect) to another space, which then uses that effect as the cause for further actions. If the handoff is synchronized well, meaning the phase alignment is ideal, the interaction is amplified, and the relay is smooth. If the handoff is misaligned, some energy is lost, and the resonance diminishes.

9.2.4 Damped Resonance

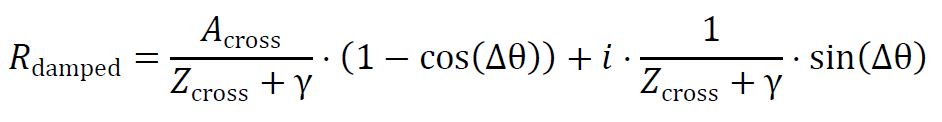

In damped resonance, interactions between processes gradually lose energy, reducing the overall amplitude of oscillations. The damping factor diminishes both the real and imaginary components of resonance, reducing oscillation amplitude without completely eliminating the oscillations.

The damped resonance (Rdamped) formula is:

Where γ represents the damping factor, accounting for energy losses in the system.

Intuition for Damped Resonance: Think of a pendulum swinging through a fluid. As the pendulum moves, resistance from the fluid slows it down, causing the oscillations to become smaller. In Natural Reality, damped resonance occurs when interactions are moderated by resistance, reducing the amplitude of the oscillations but allowing the system to maintain resonance, at a diminished level.

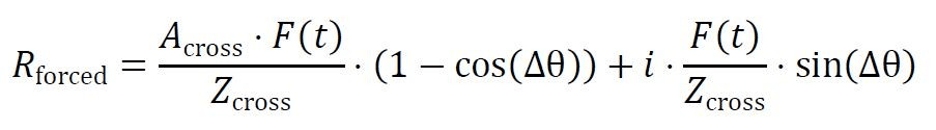

9.2.5 Forced Resonance

In forced resonance, an external process drives the system into resonance. The system is pushed into alignment by external factors that force the interacting processes to synchronize, amplifying the overall effect.

The forced resonance (Rforced) formula is:

Where F(t) is the external driving force applied to the system.

Intuition for Forced Resonance: Imagine pushing a child on a swing. If the timing of the pushes matches the swing’s natural frequency, the amplitude of the motion increases. In Natural Reality, external processes can push interacting systems into resonance, amplifying the effects when the timing is correct.

9.2.6 Phase-Shifting Resonance

Phase-shifting resonance occurs when the phase alignment between interacting processes changes. As the system’s phase alignment changes, it gradually enters resonance, allowing for amplified interactions as processes come into sync.

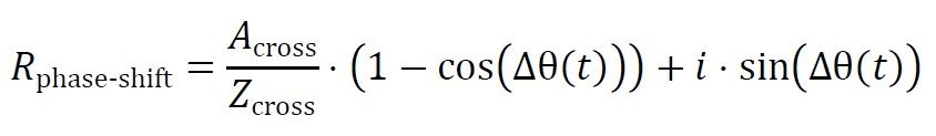

The phase-shifting resonance (Rphase-shift) formula is:

Intuition for Phase-Shifting Resonance: Consider two musical instruments that are slightly out of sync. As one instrument adjusts its timing, the two instruments gradually come into alignment, amplifying their sound. In Natural Reality, phase-shifting resonance occurs when interacting processes adjust their timing, allowing the system to naturally synchronize and amplify.

9.2.7 Nonlinear Resonance

In nonlinear resonance, small changes in the cause state lead to disproportionately large effects. This type of resonance follows nonlinear dynamics, where the system’s behavior becomes less predictable and more sensitive to initial conditions.

The nonlinear resonance (Rnonlinear) formula is:

Where f(x) represents a nonlinear function governing the system’s resonance dynamics

Intuition for Nonlinear Resonance: Think of plucking a guitar string. A soft pluck produces a gentle sound, but plucking the string harder can create distortions. Similarly, small changes in the system’s inputs can lead to outsized or unpredictable effects, characteristic of nonlinear resonance.

9.2.8 Stochastic Resonance

Stochastic resonance occurs when random variations within a system, represented as noise, help amplify resonance, allowing otherwise weak or misaligned interactions between causal spaces to synchronize. These random perturbations represent inherent variability or random fluctuations in the system’s parameters.

The stochastic resonance (Rstochastic) equation is given by:

Where:

- 𝜂fluctuation represents the stochastic noise or random fluctuation that interacts with the causal system,

- 𝐴cross is the cross-admittance,

- 𝑍cross is the cross-impedance,

- Δ𝜃 is the phase difference between causal spaces,

- The noise 𝜂fluctuation introduces perturbations in how processes interact, which can lead to amplifying weak resonances.

Intuition for Stochastic Resonance: Imagine a situation where two processes, like a conversation between two people speaking different languages, are struggling to find common ground. Normally, these processes would remain out of sync, but the presence of small, random variations (like gestures or tone changes) helps the individuals align their understanding just enough to communicate effectively. In Causal Dynamics, stochastic resonance works this way, where random fluctuations or noise in the system can help amplify interactions that would otherwise fail to resonate, pushing the processes toward alignment and helping emergence.

9.2.9 Multi-Space Resonance

Multi-Space Resonance involves the interaction of processes across multiple causal spaces (more than two), where resonance in one space influences or induces resonance in processes within other connected spaces, leading to system-wide amplification.

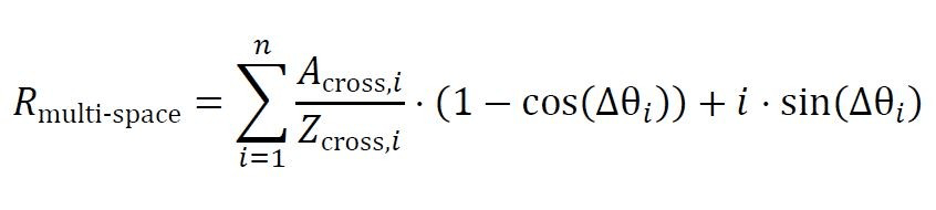

The multi-space resonance (Rmulti-space) formula is:

Where:

- I is the number of interacting processes across causal spaces,

- 𝐴cross,𝑖 and Zcross,𝑖 are the cross-admittance and cross-impedance for each process across spaces.

Intuition for Multi-Space Resonance: Imagine several interconnected oscillating systems, such as pendulums connected by springs. When one pendulum begins to oscillate at the right frequency, it can induce oscillations in the others, leading to synchronization across the system. In Natural Reality, resonance in one process within a causal space can influence other processes across spaces, leading to system-wide amplification.

9.2.10 Practical Applications of Resonance

Resonance has broad implications for real-world systems, showing how engineers, AI developers, and systems designers can harness these dynamics to enhance performance or predict emergent phenomena.

In AI systems, resonance can be used to improve model performance by aligning training data (cause) with the model’s internal learning processes (effect). By adjusting the system’s parameters to reduce cross-impedance and maximize admittance, developers can create smoother training processes and achieve more efficient learning outcomes. Feedback loops within machine learning models can be optimized for resonance, enabling faster adaptation and more accurate predictions.

Designers of resilient infrastructure systems can use resonance to synchronize energy flows or communication networks for smoother and more efficient operations. By harmonizing the rules governing different sub-systems (power grids, communication networks), engineers can reduce resistance and optimize performance, preventing failures while improving overall system stability.

Understanding how resonance drives the creation of systemic behaviors can help policymakers and economists anticipate market dynamics, environmental feedback, or social changes. By recognizing the conditions under which market actors resonate, like during periods of economic instability, predictive models can be developed to foresee economic bubbles or downturns, providing insights into mitigating their effects.

9.2.11 Synthesis

Resonance shows how systems amplify or harmonize cause-effect transitions across multiple causal spaces. The interplay between impedance, admittance, and phase alignment leads to the amplification of effects and forms a core aspect of complex system behavior. Through feedback, feedforward, damped resonance, and stochastic resonance, systems can achieve harmonization or amplification, depending on the alignment of processes.

These dynamics link to emergent behaviors in biological, economic, and technological systems. The principles of resonance provide tools for predicting and managing large-scale outcomes, whether optimizing AI performance, stabilizing energy systems, or forecasting market trends.

Resonance forms the foundation for systemic harmonization and the emergence of transformative patterns in interconnected processes.

9.3 Incoherence

Incoherence changes how processes develop by reducing or bypassing the usual penalties associated with decay. Coherent causal relationships follow the rules of a causal space and remain subject to both change and decay. Incoherence operates along a new dimension: the Causation Axis.

9.3.1 Coherent Interactions

In ideal scenarios, processes operate on the causal plane, which is governed by the rules of the causal space. These relationships are influenced by two key components: change and decay. In coherent relationships, both factors determine how influence propagates through the space, following the expected path defined by the space’s rules while maintaining constant impedance.

In this context, coherent means that the process stays on the causal plane, subject to the change and decay expected within the causal space. There is no deviation from the space’s rules, and the process doesn’t experience any alteration in impedance.

9.3.2 What is Incoherence?

Incoherence occurs when a part of the process moves off the causal plane, along a Causation Axis. This introduces a new dynamic where the process reduces or avoids the penalties associated with decay. Incoherence maintains the process within the original causal space while the incoherent part behaves differently, experiencing new states where causal impedance has changed.

This change is proportional to the process’s impedance movement along the Causation Axis. The incoherent part no longer experiences the same decay as the rest of the process within the original space. Instead, it follows a new set of rules. The process remains connected to the original space, so while part of the process operates incoherently, the rest adheres to the original space’s rules.

9.3.3 The Causation Axis

The Causation Axis represents the dimension along which Incoherence occurs. When a process becomes Incoherent, it moves off the causal plane and experiences a different impedance relative to the space’s rules. This new direction allows the process to reduce or bypass decay while still being linked to the original causal space.

The entire process doesn’t leave the original space. Instead, the part that behaves incoherently gains a higher impedance relative to the original space’s rules. This aspect of the process is less affected by decay and follows a different trajectory within the new set of conditions.

9.3.4 Incoherence as Decay-Agnostic

Incoherence is decay-agnostic, meaning it doesn’t directly engage with decay in the way that coherent processes do. The more decay-agnostic a process becomes, the more incoherent it is. This quality of Incoherence allows processes to sidestep the usual costs of interaction, experiencing less decay while still undergoing change.

Incoherence is neither inherently constructive nor destructive. It represents a deviation from the normal, coherent interactions. Its consequences, whether positive or negative, depend on the larger system and the context in which the Incoherent interactions occur. This property enables more complex behaviors, including emergence.

9.3.5 Quantifying Incoherence

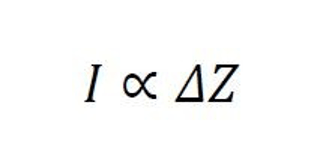

We can quantify Incoherence by measuring the change in causation impedance before and after the process changes. The degree of Incoherence is proportional to the change in impedance, as expressed in the following equation:

Where:

- I represents the degree of Incoherence,

- 𝛥𝑍 is the change in causal impedance before and after the process shifts.

The quantification models Incoherence and analyzes how processes develop when they deviate from the normal causal plane. By observing changes in impedance, we can track the extent of Incoherence and its effects on the process’s overall behavior.

9.3.6 Applications of Incoherence

This framework helps us understand phenomena in many fields where traditional causal models fall short.

Consider digital transformation. Online retail bypassed location, inventory display, and in-person sales. From the perspective of existing retail, the model was Incoherent. That Incoherence accumulated into a new layer of commerce that reshaped entire industries.

In biology, feathers first appeared for insulation or display. They had nothing to do with flight. From a locomotion perspective, growing feathers was Incoherent. As those changes harmonized with lighter bones and stronger muscles, they accumulated into an entirely new capability.

Antibiotic resistance follows the same pattern. A mutation that resists treatment operates Incoherently with normal bacterial function. Under selection pressure, that Incoherence accumulates until resistant strains dominate.

In learning, breakthroughs arrive when established approaches fail entirely. A student abandons previous methods and tries something unrelated to prior attempts. The insight is Incoherent with the old logic. That makes it generative.

Each case shows the same dynamic. What is Incoherent with local logic becomes the seed of a new one.

9.3.7 Synthesis

Incoherence expands the framework of Causal Dynamics, revealing new pathways for how processes develop and interact across causal spaces. It introduces a dimension of interaction that challenges conventional assumptions about decay and persistence, offering insights into both theoretical models and real-world applications. From designing resilient systems to identifying moments of transformation, this concept provides a way to analyze changes that defy traditional rules.

Certain processes bypass decay, allowing them to persist, adapt, or transform under conditions that would otherwise impose limits. Incoherence helps resolve paradoxical or unpredictable phenomena, showing how systems can change, reorganize, or even thrive in environments that would normally constrain them.

By revealing how systems maintain resilience or undergo radical change, Incoherence is essential to understanding emergence and harmonization. Dynamic systems realign, adapt, and interact in ways that enable transformations that wouldn’t be possible through sequential causality alone.

9.4. Emergence and Harmonization

In Natural Reality, processes interact within and across Natural Spaces, producing emergent behaviors that can’t be reduced to individual components.

Complexity describes system behaviors that emerge when multiple causal processes, each governed by distinct rules within their respective causal spaces, interact. When processes operate across spaces, new dynamics develop, creating novel behaviors or properties impossible for isolated processes.

The study of emergence and harmonization reveals how complex behaviors develop. Emergence occurs when new system properties arise through the interaction of processes, while harmonization describes how these processes adjust to create productive relationships, allowing cause-effect interactions to propagate across boundaries.

9.4.1 The Concept of Emergence

Emergence occurs when novel system-wide behaviors develop through interactions that transcend the properties of individual processes. These emergent behaviors are a direct consequence of processes harmonizing, enabling efficient propagation of causes. Resonance between processes amplifies these behaviors, leading to complexity.

Mathematically, emergence can be modeled by examining how resonance between processes reaches a critical threshold.

Where:

- 𝐸emergence represents the point at which emergent behavior occurs,

- 𝑍cross is the cross-impedance between causal spaces,

- Φ is the phase difference between their governing rules.

Emergence occurs when cross-impedance is minimized and phase alignment reaches a sufficient level, amplifying effects and producing system-level properties unattainable by individual processes alone.

To capture the full complexity of cross-space dynamics, this equation is extended by incorporating the orthogonality of process relationships, modeled using complex numbers to reflect both real and imaginary components of the phase difference:

Where:

- Δ𝜓 represents the imaginary component of the phase difference due to orthogonal induction, reflecting the cross-dimensional interaction introduced by complex phase shifts.

The refined model incorporates both real and imaginary contributions to phase alignment, capturing the full dynamics between processes.

9.4.2 Fueled by Incoherence

Incoherence, typically interpreted as a form of misalignment, can also play a pivotal role in emergence. Perfect alignment leads to predictable, stable behaviors, while Incoherence introduces innovation and the generation of new, complex dynamics.

Emergence, in many cases, results from the interplay of aligned and misaligned processes, allowing the system to explore novel configurations and behaviors.

To quantify the role of Incoherence in emergence, we model the impact of misalignment on systemic behavior:

Where:

- Δ𝑍cross represents the difference in cross-impedance between interacting processes due to Incoherence,

- 𝑅feedback is the resonance between the processes.

Controlled Incoherence can generate the tension necessary for emergent behaviors, transforming potential instability into opportunities for innovation.

9.4.3 Harmonization

Harmonization describes the dynamic process through which interacting processes align their governing rules to reduce cross-impedance and phase differences. As processes harmonize, causes propagate more efficiently between them, resulting in smoother cause-effect transitions and contributing to the creation of new behaviors.

A critical aspect of harmonization is its ability to tolerate a certain degree of Incoherence. While complete alignment is rarely possible or even desirable, maintaining a balance between alignment and misalignment fosters emergent complexity. Harmonized systems are resilient, adaptive, and capable of generating new, innovative behaviors even when confronted with disruptions.

Physical Intuition for Emergence and Harmonization: A real-world example can provide clarity on the relationship between emergence, harmonization, and Incoherence. Imagine a team working on a project. If all team members perfectly align in their thinking and actions, progress can be smooth, but the result might lack creativity. If the team members disagree too much, progress can stall entirely. The key is to find a balance where different ideas interact productively, generating innovative solutions. The creative tension (Incoherence) in their collaboration can lead to outcomes that no individual could have produced alone. The example illustrates emergence in complex systems through harmonized interactions.

Causal Dynamics provides a framework for directing interactions across causal spaces. Using induction, resonance, and Incoherence, we can influence the development of complex systems in nature, society, and technology.

9.5 Theoretical Case Studies

These case studies apply the principles of cross-impedance, feedback loops, and Incoherence to concrete scenarios. While minimizing cross-impedance might look like the most efficient approach, Incoherence can drive emergence, enabling adaptation where strict alignment would fail.

Each case examines how impedance and phase alignment influence interactions across causal spaces. By quantifying these dynamics, we reveal how biological, economic, and social systems navigate internal tensions and produce emergent behaviors.

Each case study assigns values to process impedance (resistance within a space), cross-impedance (resistance between spaces), and phase alignment (the degree of synchronization between their governing rules). These values serve as theoretical approximations, illustrating how different processes interact.

We present three distinct scenarios:

- Poor causal alignment, where misaligned rules create significant resistance.

- Moderate alignment, where partial synchronization allows for limited interaction.

- Harmonized causal flow, where low impedance and high synchronization facilitate efficient interaction.

9.5.1 Explanation of Values

In each case study, the values for cross-impedance and phase alignment reflect how effectively causes from one space can propagate into the other. The following considerations guide the assignment of values:

- Cross-Impedance (Zcross): Quantifies the difficulty of causal transfer between two spaces. A higher cross-impedance (Zcross ≈ 0.8) means that the governing rules of the spaces are significantly different, making causal flow difficult. A lower cross-impedance (Zcross ≈ 0.2) indicates greater compatibility between the spaces, allowing for smoother causal flow. The assigned values in each case study illustrate how different degrees of causal rule divergence impact interaction.

- Phase Alignment (ϕ): Reflects how synchronized the governing rules of the two spaces are. Perfect alignment (ϕ = 0) means the rules are fully in sync, allowing for maximum causal efficiency. Poor alignment (ϕ = π) means the rules are completely out of phase, leading to maximum resistance. Intermediate values (ϕ = π/2) indicate partial alignment. In these examples, the phase alignment is symmetric in both directions between spaces.

- Asymmetry in Cross-Impedance: Cross-impedance values can differ depending on the direction of causal flow. Short-term decisions can more easily influence long-term outcomes than the reverse, as demonstrated in the first case study. This asymmetry in cross-impedance is modeled by assigning distinct values for cross-impedance in each direction of causal flow.

The values are illustrative, but each space is well-modeled and the governing rules are known. As causal spaces are refined and better understood, more precise values can be determined based on empirical data or detailed simulations.

9.5.2 Case Study 1: Short-Term vs. Long-Term

This case models the ongoing tension between short-term gratification (red space) and long-term health (blue space). The cross-impedance in this scenario arises from the contradictory rules governing immediate rewards (e.g., eating sugary foods) and sustained health benefits (e.g., dietary discipline).

In our first case study, the blue space represents long-term rewards: decisions and behaviors that prioritize future benefits, such as health, savings, or delayed gratification. The red space represents short-term gratification, where the focus is on immediate rewards, such as indulgence in pleasure or impulsive decisions. These two spaces operate under different causal rules: the blue space emphasizes long-term thinking and delayed outcomes, while the red space is driven by immediate rewards and rapid feedback. The interaction between these spaces often leads to conflict, as the priorities of one space are at odds with the other, but they don’t exert equal influence.

- Phase Alignment (ϕ): The phase alignment between the blue space (representing long-term rewards) and the red space (representing short-term gratification) is poor (ϕ = π), reflecting the strong misalignment between short-term and long-term priorities.

- Cross-Impedance (Zcross): The cross-impedance from the blue space to the red space (long-term to short-term) is high, with Zcross= 0.8, indicating significant resistance to long-term priorities influencing immediate decisions. In the reverse direction, from the red space to the blue space, the cross-impedance is slightly lower at Zcross = 0.6, meaning that immediate rewards have a somewhat easier path in affecting long-term planning.

With a phase alignment of π, the effective impedance is maximized from long-term priorities (blue space) to short-term decisions (red space), making it very difficult for long-term benefits to influence immediate gratification. Due to the asymmetric cross-impedance, immediate rewards (red space) still exert more influence over long-term planning, though this influence is limited. The high cross-impedance of 0.8 from long-term to short-term restricts this influence, while the lower cross-impedance of 0.6 from short-term to long-term allows short-term rewards to more easily disrupt long-term strategies.

Causal Model and Quantification

The impedance between these two causal spaces is represented mathematically as:

Where:

- 𝑍cross is the cross-impedance between short-term and long-term motivations,

- 𝐴long-term represents the admittance of long-term benefits (how easily long-term benefits propagate),

- 𝐴short-term represents the admittance of immediate rewards (how easily short-term rewards propagate).

When this is high, the system becomes entrenched in immediate gratification, making it difficult for long-term health goals to take root. By introducing small adjustments (e.g., healthy alternatives that still provide instant gratification), we can modulate the cross-impedance, leading to a gradual realignment of the system.

Rearranging the Inductive Feedforward Path

To harmonize these spaces, we manipulate the system by creating incentives that guide short-term actions toward long-term benefits. The adjustment changes the inductive feedforward path between the spaces, moving impedance away from the red space toward the blue space. By embedding long-term motivations in short-term actions (e.g., introducing healthy, yet gratifying behaviors), we change the system’s focus to long-term health.

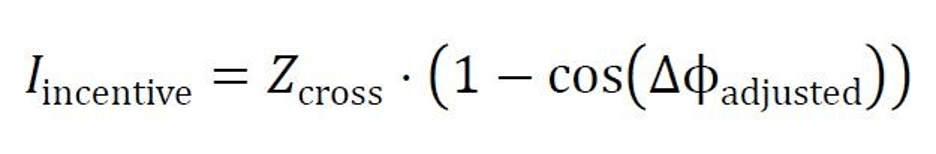

The revised inductive feedforward model can be expressed as:

Where:

- 𝐼incentive represents the impedance shift from introducing incentives,

- Δϕadjusted is the phase alignment between short-term actions and long-term motivations post-adjustment.

By reducing Δϕadjusted, we bring the two spaces into better phase alignment, minimizing impedance and creating an efficient pathway for long-term health benefits to emerge through immediate actions.

Harmonization and Emergence

The adjustment harmonizes the two causal spaces. By realigning incentives, we reduce cross-impedance and create a system where immediate actions are more likely to support long-term health outcomes. Emergent behaviors follow, such as consistently choosing healthier options that wouldn’t have arisen from short-term focus alone.

9.5.3 Case Study 2: Exercise vs. Nutrition

We explore the dynamic interplay between exercise (blue space) and nutrition (red space). While the physiological benefits of exercise emerge in the long-term, they rely on immediate nutritional support for recovery and adaptation.

The interaction between the blue space, representing exercise, and the red space, representing nutrition, follows complementary causal rules, where physical activity increases the demand for nutrients, and proper nutrition enhances physical performance and recovery, boosting the effectiveness of exercise. The interaction between these spaces is highly cooperative, with both spaces reinforcing each other.

- Phase Alignment (ϕ): The phase alignment between the blue space (exercise) and the red space (nutrition) is high, with ϕ ≈ π/10, meaning that the priorities of physical fitness and nutritional intake are well-aligned. The phase alignment is symmetric in both directions, allowing for a reinforcing feedback loop between exercise and nutrition.

- Cross-Impedance (Zcross): The cross-impedance between the spaces is low. Zcross = 0.2 shows that exercise and nutrition work in harmony, with little resistance to the causal flow from exercise benefiting from improved nutrition. In the reverse direction, Zcross = 0.1 highlights how easily nutritional improvements enhance physical performance.

In this example, the strong phase alignment and low cross-impedance between exercise and nutrition lead to an efficient and reinforcing interaction between the spaces. Improvements in one space directly support and amplify benefits in the other, creating a harmonious system.

Causal Model and Quantification

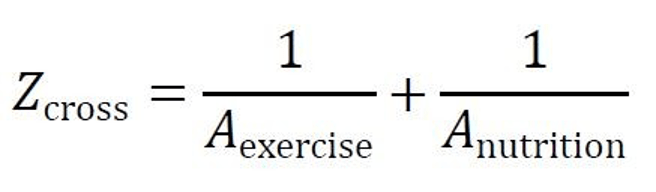

The relationship between exercise and nutrition can be modeled as an interaction between causal spaces, with feedback loops reinforcing systemic health benefits. The impedance equation for this scenario is:

Where:

- 𝑍cross represents the cross-impedance between the exercise (blue) and nutrition (red) spaces,

- 𝐴exercise is the admittance from the exercise regime (ease of physical adaptation),

- 𝐴nutrition is the admittance from nutritional input (ease of recovery).

If cross-impedance is high due to misalignment (e.g., poor nutrition post-exercise), the overall benefit of exercise diminishes. By aligning exercise routines with optimal nutrition, we reduce cross-impedance, allowing for the emergence of enhanced fitness and recovery.

Oscillations in Recovery and Feedback Loops

Each exercise session creates a feedback loop in the body, where recovery (caused by nutrition) reinforces the physiological effects of exercise. This feedback loop oscillates, especially in systems with periodic workouts (e.g., daily exercise routines). If exercise and nutrition are not aligned, cross-impedance rises, reducing the effectiveness of the workout.

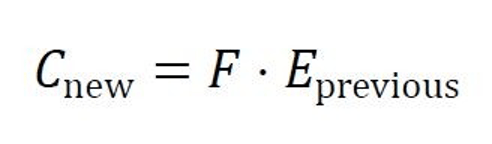

We can model this feedback loop as:

Where:

- Cnew is the new nutritional cause generated by the previous effect (Eprevious) of exercise .

- F is the feedback factor representing how much of the exercise effect is retained and converted into a need for nutrition.

Harmonization and Emergence

By aligning nutritional intake with exercise routines, we reduce cross-impedance and increase the system’s overall admittance. The harmonization creates emergent behaviors like improved endurance, muscle growth, or metabolic adaptation, which are greater than the sum of the individual effects of exercise or nutrition alone. A well-harmonized system can achieve emergent health outcomes by minimizing impedance and optimizing feedback loops between exercise and nutrition.

9.5.4 Case Study 3: Market and Consumer

This case models the misalignment between rapidly changing market dynamics (blue space) and slower-developing consumer perception (red space). Market signals often change faster than consumer behavior, creating high cross-impedance that leads to inefficiency.

The red space represents consumer perception, which includes expectations, mental models, and ingrained habits that shape how individuals respond to external information. The blue space represents market dynamics, encompassing pricing changes, supply changes, and emerging economic conditions. These two spaces follow distinct causal rules: the blue space operates dynamically, adjusting rapidly based on demand and supply fluctuations, while the red space is slower-moving, shaped by past experiences, habitual behaviors, and psychological inertia.

- Phase Alignment (ϕ): The phase alignment between market dynamics (blue space) and consumer perception (red space) is moderate, with ϕ ≈ 2π/3. This indicates that while consumers respond to market conditions, their adaptation lags behind, creating resistance to rapid economic changes.

Cross-Impedance (Zcross): The cross-impedance from market dynamics to consumer perception is moderate to high, at Zcross = 0.6, meaning that pricing changes and economic signals don’t immediately translate into changes in consumer behavior. The cross-impedance from consumer perception to market response is lower, at Zcross = 0.4, indicating that changes in consumer habits can gradually influence the broader market but not as abruptly as market changes influence consumers.

With a phase misalignment of 2π/3, the system experiences delayed synchronization between market signals and consumer adaptation, creating inefficiencies such as supply-demand mismatches or delayed policy effectiveness. The higher cross-impedance from blue to red means that changes in pricing, trends, or new product launches take time to be absorbed by consumer perception, while established consumer behaviors can reinforce market patterns over time due to lower impedance in the reverse direction.

The interaction highlights the asymmetry in market perception dynamics. Businesses struggle to change consumer expectations quickly, but once an expectation is formed, it exerts a stabilizing effect on market behavior. This asymmetry is essential in branding, behavioral economics, and economic forecasting, where interventions need to account for delayed but lasting consumer adjustments.

Causal Model and Quantification

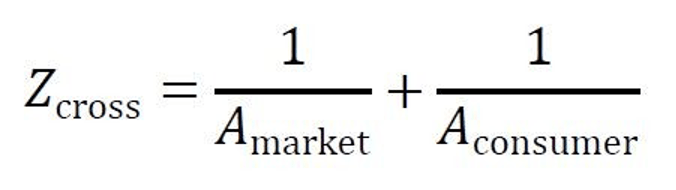

We quantify cross-impedance in this system as:

Where:

- 𝑍cross represents the cross-impedance between market dynamics and consumer perception,

- 𝐴market is the admittance from market signals (ease of interpreting market shifts),

- 𝐴consumer is the admittance from consumer behavior (ease of responding to market changes).

Feedforward Dynamics

Market dynamics can create feedforward loops, where rapid changes in supply, demand, or pricing (blue space) fail to induce a response from consumers (red space). When the cross-impedance is managed effectively, emergent properties such as consumer loyalty or market stability can arise, transforming misaligned spaces into harmonized, adaptive systems.

The feedforward model is expressed as:

Where:

- Emarket represents the effect of market changes as seen in consumer behavior.

- Cmarket is the market cause (e.g., pricing changes or new products).

Harmonization and Emergence

By synchronizing market signals with consumer perception, businesses can reduce volatility and achieve emergent outcomes such as brand loyalty and stable growth. The system reaches a state of harmonization when the lag between market changes and consumer reactions is minimized, allowing for smoother causal flows across spaces. The emergent properties, such as market predictability and consumer trust, arise from the effective harmonization of these dynamic spaces.

Reverse Induction and Systemic Adaptation

While initial impedance between market signals and consumer perception can create inefficiencies, these systems tend to self-correct over time through reverse induction, a process in which effects reshape their originating causes. As consumer behavior gradually adapts to changing economic conditions, businesses also refine their strategies based on observed patterns, effectively modifying the causal structures that govern market interactions. The recursive adjustment process fine-tunes phase alignment and reduces impedance dynamically, leading to emergent properties such as sustained brand loyalty, stable demand cycles, or improved policy effectiveness.

9.5.5 Proposed Case Studies and Empirical Validation

The application of Natural Reality across various fields reveals how distinct causal spaces can interact, creating opportunities for system optimization. Below are examples of how these principles can be applied, along with proposed empirical studies to validate the theoretical models.

Neural Networks and Cognitive Processes

In cognitive neuroscience, the blue space represents lower-level neural processes (e.g., synaptic plasticity, neuron firing patterns), while the red space represents higher-level cognitive functions such as memory retrieval or decision-making. Misalignments between these levels appear as cognitive dysfunctions or delays in decision-making.

Studies using fMRI or EEG data can model the cross-impedance between neural activity and cognitive performance, quantifying how neural misalignments affect cognition. This data enables researchers to test interventions aimed at harmonizing neural activity with cognitive functions, potentially improving mental performance or addressing cognitive disorders.

Supply Chain and Market Dynamics

In global supply chains, the blue space represents logistical and operational constraints, while the red space reflects fluctuating market demands. Misalignments between supply chain capabilities and market pressures often create bottlenecks or inefficiencies.

Simulations model interactions between supply chain logistics and market conditions, quantifying cross-impedance in terms of supply disruptions or delays. Testing harmonization strategies, such as adaptive learning algorithms, produces more reliable and effective responses to changing environments.

Artificial Intelligence in Autonomous Systems

In AI and robotics, the blue space represents the internal decision-making algorithms of an autonomous agent, while the red space represents its interaction with external environments. Misalignments between an agent’s internal model and external conditions (e.g., unpredictable environments) lead to suboptimal decisions or task failure.

Robotics or AI simulations model how cross-impedance between decision-making systems and environmental changes affects performance. Testing harmonization strategies, such as adaptive learning algorithms, ensures more reliable and effective responses to changing environments.

Public Health and Policy Implementation

In public health, the blue space represents scientific guidelines and health recommendations aimed at managing disease outbreaks, while the red space represents real-world policy implementation and public behavior. Misalignments between these spaces result in poor public health outcomes, as seen during pandemics.

Public health data and simulations quantify the cross-impedance between health recommendations and policy enforcement. Testing harmonization strategies, like improved communication channels or aligning public incentives with health goals, produces more effective disease management and better public health outcomes.

By applying Natural Reality to diverse fields and validating the models through empirical studies, researchers and practitioners can develop actionable strategies to resolve conflicts between distinct causal spaces, reduce cross-impedance, and foster harmonization. These efforts contribute to more resilient, adaptive systems across disciplines, from neuroscience and public health to AI and global supply chains.

9.5.6 Synthesis

These case studies quantify how Causal Dynamics operates in real-world systems. By applying cross-impedance, admittance, and feedforward dynamics, they demonstrate how systems resolve conflicts, adapt, and produce emergent behaviors.

Incoherence enables adaptation, revealing how novel behaviors emerge. These models show how to harness Incoherence to enhance resilience and long-term stability.

9.6 Closing Remarks

We now have equations for impedance, admittance, phase alignment, and resonance. The equations measure how influence propagates through any system.

The mathematics works like electrical engineering for causation. We calculate resistance (impedance), measure flow efficiency (admittance), and predict when systems amplify (resonance).

When processes escape normal decay patterns by changing their impedance relationships, we track that change as ΔZ and model when reorganization becomes favorable. We can calculate when emergence occurs.

The same mathematics describes learning curves, ecological dynamics, technology diffusion, and market responses. Chapter 10 applies the framework to complex systems.