Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- On Perspective

- Causation & Interpretation

- Principles of Natural Reality

1. Preface

Why study “reality”?

Because it gives you superpowers!

I’ll explain.

An Electrical Circuit

An engineer designs an electrical circuit. When the load increases, the voltage at the power source drops. To address this, the engineer adds a capacitor in parallel with the source. The capacitor stores electrical energy and absorbs voltage drops in proportion to the amount of energy it holds. The larger the capacitor, the greater the fluctuations the circuit can handle.

Water Supply

A city distributes water from a river to its residents. When there’s a drought, the river level drops. To address this, the city adds a dam in parallel with the river. The dam stores water and absorbs river level drops in proportion to the amount of water it holds. The larger the dam, the greater the fluctuations the city can handle.

Personal Finances

I have bills to pay. When my bills increase, the money in my checking account drops. To address this, I add a savings account in parallel with my checking account. The savings stores money and absorbs cash shortages in proportion to the amount of money it holds. The larger my savings, the greater the fluctuations I can handle.

See any patterns?

On the surface, things like electrical circuits, rivers, and bank accounts might appear to be worlds apart, yet they can behave identically in the causation domain of the Universe.

Principles describes reality in this so-called “causation domain.”

When you study Principles, you’ll learn to see the invisible, reconcile paradoxes, design sustainable realities from the ground up, and much more.

Welcome to Natural Reality!

2. Introduction

Principles of Natural Reality is the ultimate theory of everything.

It models the operation of the observable Universe, describes the emergence of things, andserves as a master blueprint for reality in any context.

This book has three parts.

The first part defines the “outside-in” perspective of Principles.

In the second part, Causation & Interpretation introduces concepts that make Principles easier to understand. Starting from a proverbial apple falling from a tree:

- Reconciliation of Paradoxes explains how theories and models of natural phenomena are selected based on their ability to solve paradoxes;

- Across Natural Spaces describes observations and interpretations made across Natural Spaces. It emphasizes distinctions between events caused by other events, and events produced in response to other events; and

- How Incoherence Gives Rise to Paradoxes highlights the importance of perspective for appreciating Incoherence as a property of Natural Reality, and shows how paradoxes arise in the mind of an observer.

In the third part, Principles describes the state of things as they are.

More specifically, Principles models the operation of the observable Universe in the causation domain along the axis where emergence happens.

Regardless of whether Principles merits recognition as a formal scientific theory, I suspect its Natural Reality Model will remain useful in various fields of human endeavor.

And I hope you will enjoy it in your personal life, too!

“Happy the man who has learned the cause of things and has put under his feet all fear, inexorable fate, and the noisy strife of the hell of greed.”

— Virgil (70–19 BC).

Thank you for reading this work.

Principles is the most ambitious Abstractionist job ever attempted, and it represents the culmination of a life dedicated to the practice of seeing depth.

3. On Perspective

Inside-Out vs Outside-In

To the extent human beings have not produced useful answers about reality to this day, it is not because of a lack of scientific discoveries or philosophical observations.

Rather, it is due to our naïve insistence on approaching the subject with an inside-out perspective.

From the inside-out, reality is intractable.

A theory of reality devised with an inside-out perspective would have to account not only for what is observable, but also for the observer’s imagination (i.e., the conceivable) and limitations (i.e., the inconceivable).

These are impractical, self-defeating requirements.

To address this, I wrote The Baroness and the Abstractionist.

Through storytelling, The Baroness provides an alternative way of seeing that works: the outside-in perspective, the same perspective Nimbin uses to study the Toy Maker’s model.

With an outside-in perspective, Principles concerns itself exclusively with what is observable, and disregards everything that is not observable.

As a reminder of this, Principles uses the term “Natural Reality.”

(Incidentally, the inner workings of Nimbin’s Opera Glasses have been disclosed in U.S. Patent Application Pub. No. 2023/0222704, Systems and Methods for Visualizing Natural Spaces Using Metaverse Technologies.)

4. Causation & Interpretation

Reconcilation of Paradoxes

Here is an anecdote:

“A cool October breeze rustles the leaves of an apple tree.

Sunlight swirls through its branches, casting a golden glow on the fruits that dangle delicately from their stems.

Thira’s gaze fixates on one particular apple, its vibrant red skin shimmering against the day’s magic hour.

Little by little, the apple loosens its grip on the branch, as if surrendering to an invisible pull.

Splat!

All of a sudden, the apple falls to the ground.”

The way in which an apple falls from a tree is prescribed by a Rule of Causation.

Rules of Causation are enforced in the causation domain of the observable Universe.

After 1686, we learned to interpret this particular Rule as gravity.

Much before gravity was ever described as such, however, apples already fell from trees in exactly the same manner.

That is because regardless of what interpretation we may adopt, it is the application of the same underlying Rule of Causation that makes the apple fall to the ground.

But of course, interpretation matters.

Before Newton, less sophisticated interpretations gleaned from day-to-day experiences, more along the lines of “lack-of-vertical-support-causes-things-to-fall,” were all we had available to explain these types of events.

Lack-of-vertical-support may satisfactorily how an apple falls from a tree, but it also gives rise to paradoxes—propositions that, despite seemingly sound reasoning from acceptable premises, lead to conclusions that are contradictory, logically unacceptable, or senseless.

For example, lack-of-vertical-support fails to explain how the Sun stays up in the sky.

In contrast, Newton’s gravitational model successfully explains how an apple falls and how the solar system works, without paradoxes.

So it goes, new models and theories about natural phenomena appear thanks to human invention.

Among those, better ones are selected by our species (as accepted reality) to the extent they reconcile paradoxes.

Across Natural Spaces

In response to light bouncing off the surface of an apple and reaching Thira’s eyes, her brain deduces a visual image.

The image of the apple produced by Thira’s brain is an abstraction of the physical apple before her.

Incontestably, the physical apple and its image are distinct entities.

If Thira closes her eyes, the image disappears but the physical apple remains.

That is because the physical apple and the visual image of the apple are hosted in different Natural Spaces.

The physical apple inhabits our shared, physical Natural Space, whereas the visual image of the apple is produced in an individual, abstract Natural Space of Thira’s mind.

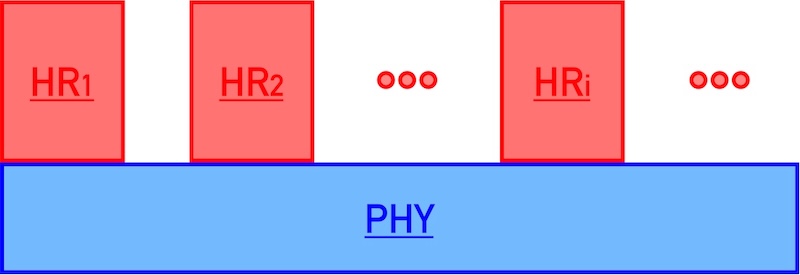

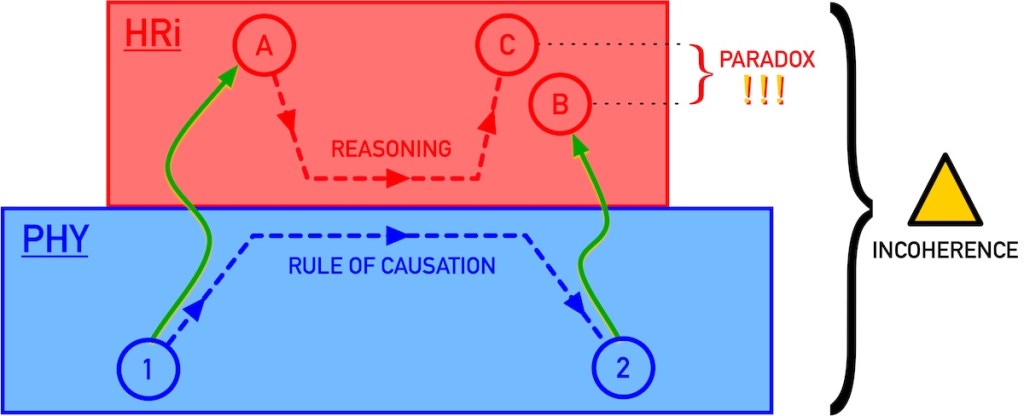

For brevity, let us refer to the individual abstract reality of Thira’s mind as “HRi” and to the shared physical reality of the observable Universe as “PHY.”

Also, for ease of visualization, let us designate red for HRi and blue for PHY, such that a two-layer Natural Reality Model may be illustrated as:

When the apple falls from the tree, Thira’s mind produces HRi based on her observations and interpretations of the physical phenomena taking place in PHY.

(1) Thira’s Observations

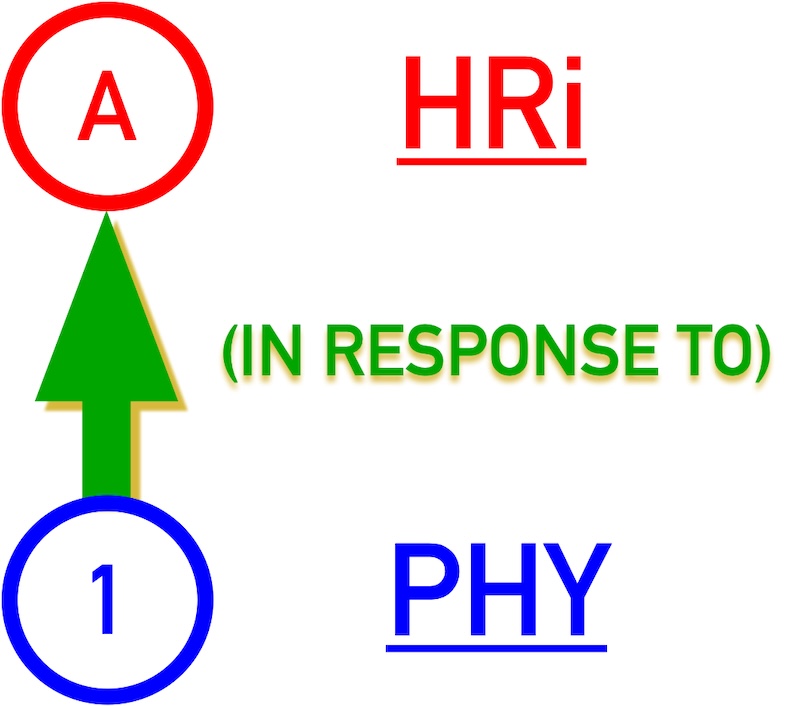

In PHY, ➀ represents the physical apple hanging from the tree:

In HRi, Ⓐ is an abstraction produced in Thira’s mind in response to her perception of ➀.

For example, Ⓐ may be the visual image of the apple hanging from the tree.

After the apple falls, in PHY, ➁ represents the physical apple on the ground:

In HRi, Ⓑ is an abstraction produced in Thira’s mind in response to her perception of ➁.

For instance, Ⓑ may be the visual image of the apple splat on the ground.

In sum,

Ⓐ is produced in response to ➀, and Ⓑ is produced in response to ➁. Neither is Ⓐ caused by ➀, nor is Ⓑ caused by ➁. Rather, both Ⓐ and Ⓑ are caused by … Thira.

(2) Thira’s Interpretations

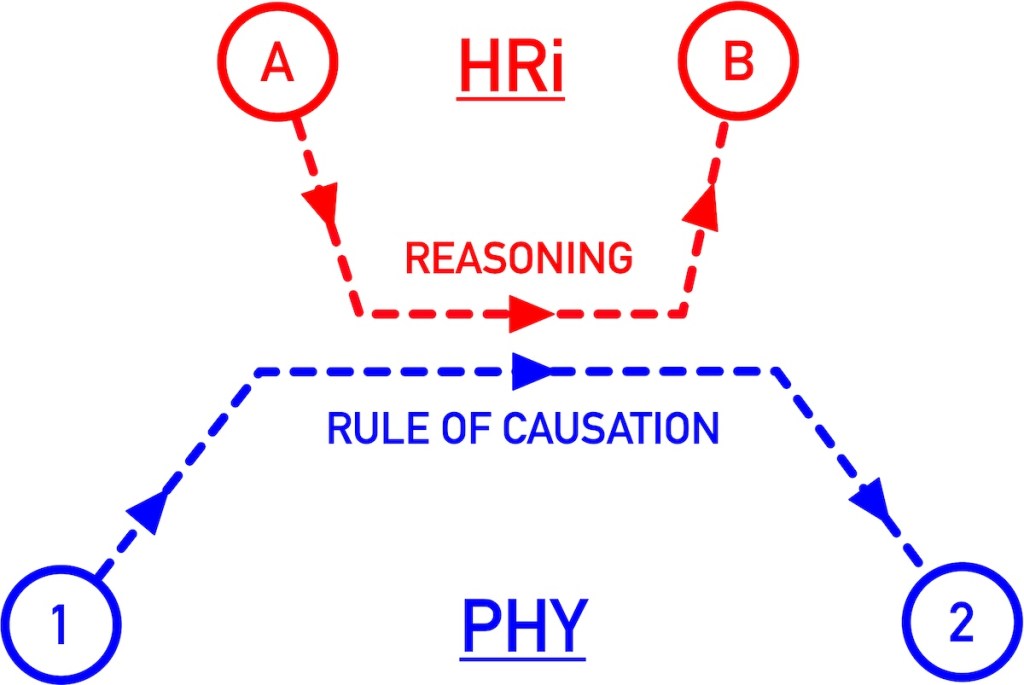

The underlying Rule of Causation that links ➀ to ➁ operates in the causation domain and is not subject to sensory perception, so it must be interpreted by Thira in HRi.

Regardless of what the underlying Rule may be, what links ➀ to ➁ in PHY (i.e., what we refer to as gravity) is not the same thing that operates on Ⓐ or Ⓑ in HRi.

After all, abstractions do not have mass.

Instead, the rule linking Ⓐ to Ⓑ in HRi is Thira’s reasoning:

Thira’s reasoning depends on whatever ideas she can produce in HRi (e.g., gravity, lack-of-vertical-support, “what-goes-up-must-come-down,” etc.).

Absent invention, Thira’s ability to produce those ideas depends on her having learned them.

How Incoherence Gives Rise to Paradoxes

Incoherence (Δ) is a property of Natural Reality that can give rise to paradoxes in a human mind making observations with an inside-out perspective.

Let us consider the scenario where Thira decides the apple fell from the tree because lack-of-vertical-support-causes-things-to-fall.

Now Thira must make sense of the fact that apples fall from trees while the Sun does not collapse to the ground:

What happens in PHY:

- In ➀, the Sun is in the sky. A Rule of Causation operates and produces ➁. Whatever that Rule may be, the Sun does not fall.

- Hence, in ➁, the Sun is still up in the sky.

What happens in HRi:

- Ⓐ is produced in response to Thira’s perception of ➀. For instance, Ⓐ may include a visual image of the Sun in the sky.

- Ⓑ is produced in response to Thira’s perception of ➁. For instance, Ⓑ may include a visual image of the Sun still in the sky.

- Thira applies reasoning to Ⓐ to produce Ⓒ. In this case, Ⓒ represents Thira’s expectation that the Sun must also fall because it is not vertically supported.

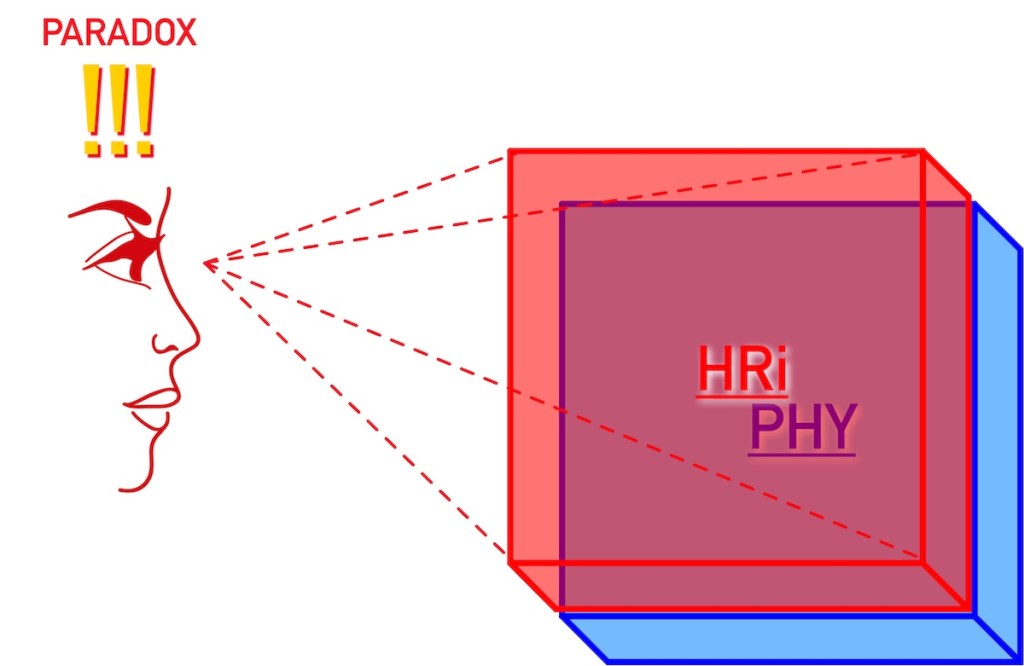

If Thira holds an inside-out perspective such that, to her, HRi and PHY are commingled, the irreconcilable conflict between expectations Ⓒ and observations Ⓑ gives rise to a paradox:

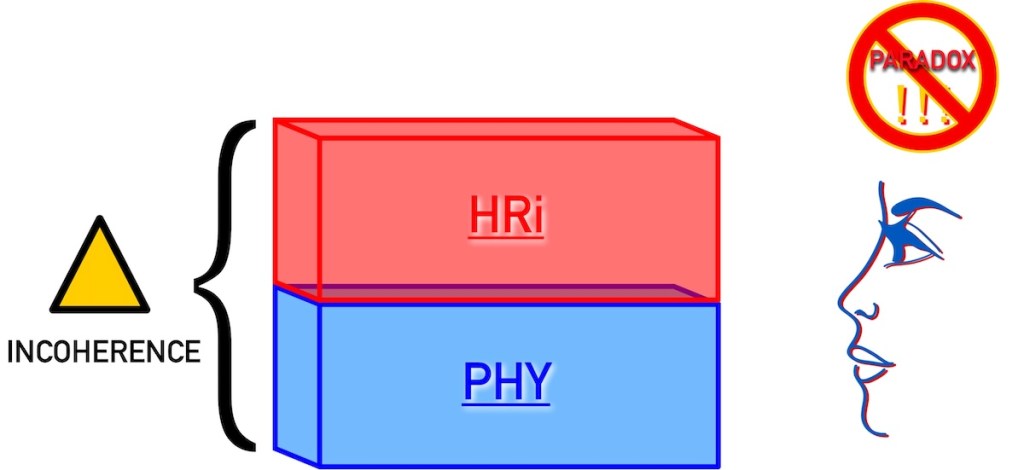

On the other hand, if Thira adopts an outside-in perspective and learns to distinguish HRi from PHY, she can acknowledge Δ and the paradox disappears:

5. Principles of Natural Reality

Abstract

Natural Reality is observed in two distinct domains:

- an Interpretative Domain; and

- a Causation Domain.

The Interpretative Domain, in its present state, comprises a plurality of Natural Spaces (e.g., subatomic, atomic, chemical, biological, abstract, etc.) operating concurrently.

The Causation Domain enables the operation and emergence of Natural Spaces.

Principles models Natural Reality in its Causation Domain.

Definitions

- A “Natural Space” is an environment containing entities that interact under the enforcement of Rule(s) of Causation.

- An “entity” is a thing subject to observation. (A “thing” is a snapshot of a process.)

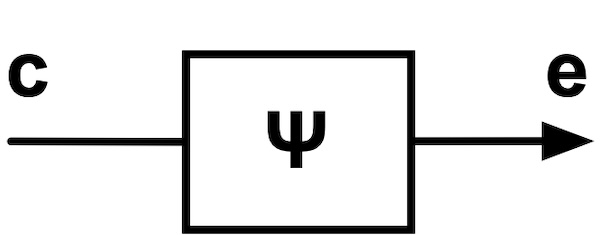

- A “Rule of Causation” (Ψ) is a rule that, upon enforcement, turns a cause into an effect, thereby enabling interactions between entities.

- A “cause” (c) is an event or state that produces a result under enforcement of a Rule of Causation.

- An “effect” (e) is an event or state that results from of a cause, as produced under enforcement of a Rule of Causation.

- An “Interaction” is an event whereby entities affect one another.

- “Change” (δ) relates to the act or instance of making or becoming different.

- “Decay” (λ) relates to the act or instance of making or becoming non-observable.

Natural Spaces

Natural Reality presents itself through the concurrent operation of a plurality of Natural Spaces.

In a Natural Space:

- Entities interact;

- Interactions produce, in each participating entity, change (δ) and decay (λ); and

- As a consequence of (1) and (2):

“If a changed entity combats decay more effectively than other entities, by virtue of prevailing over the other entities, the changed entity is deemed to have been selected.”

— Principle of General Selection.

Interactions

In a Natural Space, enforcement of Rule of Causation (Ψ) turns cause (c) into effect (e):

Ψ: c → e, where e = δ + λ.

For each Interaction:

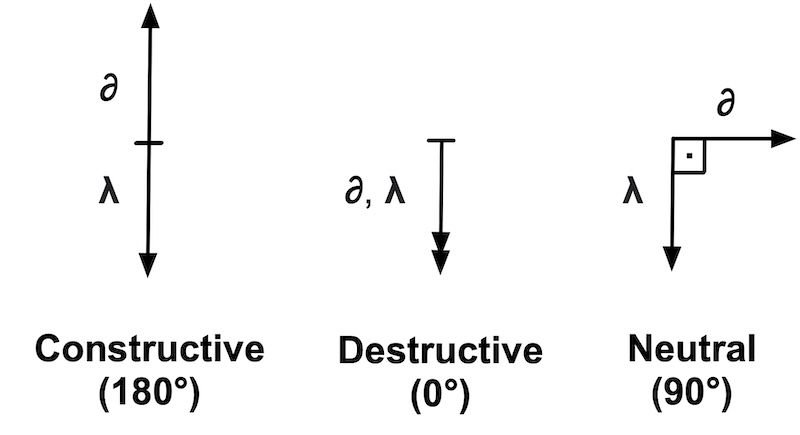

- If δ negates λ (180°), e is deemed constructive;

- If δ affirms λ (0°), e is deemed destructive; and

- If δ does not affect λ (90°), e is deemed neutral.

Causation Impedance

An entity’s immunity to the application of Ψ is referred to as its Causation Impedance (Z) with respect to Ψ, or ZΨ.

For an entity having ZΨ, the result of an Interaction governed by Ψ is given by:

c ∝ ZΨ x e.

Hence, for a fixed c:

- Entities having a larger ZΨ are less susceptible to Ψ, therefore are subject to a smaller e; and

- Entities having a smaller ZΨ are more susceptible to Ψ, therefore are subject to a larger e.

Note:

- Compare with F = m x a (Newton) or V = R x i (Ohm).

Incoherence

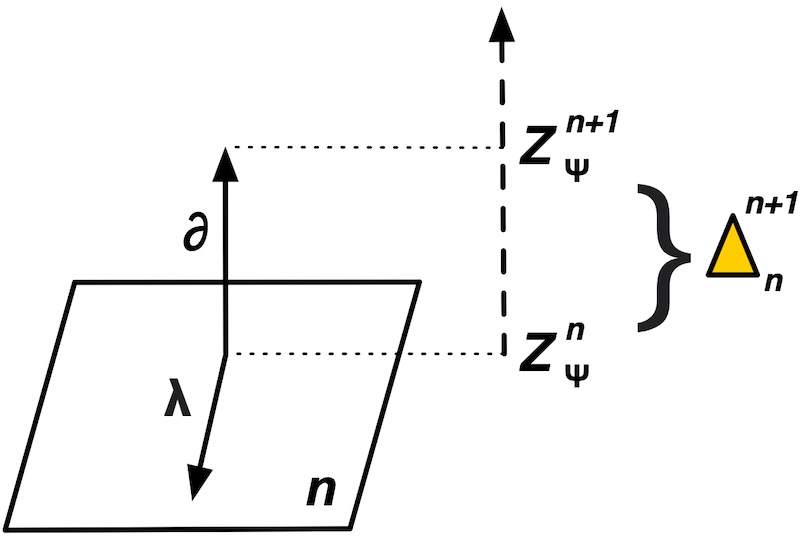

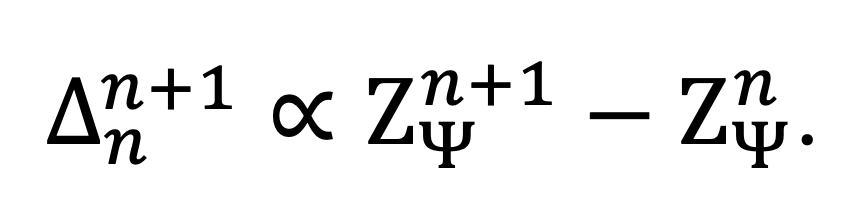

Incoherence (Δ) is produced when δ increases an entity’s ZΨ, thus allowing that entity to escape the application of Ψ.

Once General Selection produces a sufficient accumulation of Δ, changed entities emerge from their Natural Space (n) and interact with like entities, at least in part, effectively governed by different Rule(s) of Causation:

where:

The Emergence of Natural Spaces

From the bottom up:

- In a first Natural Space (n-1) (a “blue space”), entities of a first type (“blue entities”) having Zn-1 interact with each other governed by Ψn-1;

- Through application of General Selection, accumulation of Δ among blue entities yields entities of a second type (“green entities”) having Zn;

- Green entities interact with each other governed by Ψn, thus forming a second Natural Space (n) (a “green space”) overlying the blue space;

- In the green space, green entities continue to undergo General Selection. As a result, accumulation of Δ among green entities yields entities of yet another, third type (“red entities”), having Zn+1; and

- Red entities interact with each other governed by Ψn+1, thus forming a third Natural Space (n+1) (a “red space”) overlying the green space, and so on.

A Natural Space persists so long as:

- δ successfully combats λ, both in that Natural Space and in its underlying Natural Space(s); and

- Across Natural Spaces, Δ remains sufficiently harmonized.

A Contextualization Exercise

Let us discretize three Natural Spaces by modeling each of them to include entities of a selected type, and to exclude any entity of any other type.

With these approximations:

- Atomic entities (and astronomical bodies) may be deemed to inhabit a first Natural Space having a physical character (a “blue space”);

- The biological world may be deemed to constitute a second Natural Space made of entities defined as living or organic (a “green space”); and

- Each biological entity’s mind may be deemed to amount to a third Natural Space made of abstract entities (a “red space”).

Notes:

- In a human mind, abstract interpretations of the blue, green, and red Natural Spaces are effectively (and inadvertently) commingled, and General Selection produces learning.

- In the biological world, General Selection is referred to as Natural Selection.

♦ ♦ ♦