Table of Contents

Preface

Introduction

Nimbin’s Paradox

A False Start

Out Come the Crayons

Emergence of a First Principle

The Problem with Materialism

Why You Don’t Go Back

The Eddy Network

No Way Out

Conclusion

Epilogue: Abstraction Under Pressure

Appendix A: The (Un)Happiness Letter

Appendix B: A General Theory of Reality

Appendix C: On the Human Condition

Preface

The Abstractionist’s Papers is a book about Natural Reality. This book tells you where the idea came from.

A year after publishing, readers kept asking the same question: how could something like this come from a patent attorney?

I wrote The Only Show in Town to answer it. It’s about how Natural Reality emerged and how the character I invented eight years prior became real in 2025.

First-time readers can follow along. I explain enough as I go.

Welcome to the Blue Space.

Luiz von Paumgartten, The Abstractionist

PS. If you haven’t read The Papers, Glitches in Reality covers the basics in ten minutes.

Introduction

Natural Reality began in December 2017 with a letter to my children about happiness. Two days later, a second letter tried to pin down some early ideas about reality. Most of them were wrong.

Three months after that, letters became papers and crayons appeared. Blue for the physical world. Red for human reality. The color distinction did what words alone couldn’t. The original documents are in the appendices.

In the Fall of 2018, I wrote a story titled Nimbin and The Abstractionist. The Abstractionist was a character who could take a model and show how it worked from the inside and outside at once.

By spring 2019, I was writing explanations for how he did that. Drawings on every page, a lab notebook full of ideas that became blog post after blog post. What started as a story became a description of how reality operates.

In 2023, I published Principles of Natural Reality, then pulled it. I’d built a map and called it a theory. Once I saw the difference, the book had to come down.

By early 2024, the map was complete. I released The Intact and the Flightless. The Abstractionist’s Papers came out in February 2025.

Ten months later, I went on the No Way Out podcast with Mark McGrath and Brian Rivera, two men who’ve built their careers around John Boyd’s OODA loop and its application to military strategy. We spent hours on how Natural Reality connected to problems they’d been working on for years.

In that conversation, the character I created in 2018 came to life.

All good things come from work.

Nimbin’s Paradox

In December 2017, I wrote a letter to my children from Australia.

They were still very young. The letter was for the people they would become. It addressed a future I could imagine, speaking to them as if they were sitting right beside me in an ever-present now.

I was trying to explain happiness, but I couldn’t. I sidestepped it entirely, turning to unhappiness instead.

The letter read:

“I returned to Nimbin Valley to write this letter. Earlier this year I had the idea to write an essay about happiness. My goal was simply to teach you how to be happy.

Well, it turns out that happiness is hard. There is no common thread, no single formula that can teach a human being how to be happy. To make matters worse, the more I thought about happiness, the more I realized that I didn’t even know what that meant, either.

So I eventually decided to leave happiness alone.

Instead, I chose to write about unhappiness.”

A model followed:

“The unhappiness potential of an experience, to a person, is directly proportional to the difference between that person’s expectation (E) of that experience, and the outcome (O) that corresponds to that expectation. In other terms:

Unhappiness Potential ∝ (E – O)

This model gives a qualitative indication of how negatively an experience may potentially be perceived by a person.

To reduce unhappiness, one must reconcile E with O.

Reconciliation can be done by changing E at an emotional cost, changing O at an energy cost, or, in practice, by doing a combination of both.

There is no other way.

Without reconciling E with O, the experience becomes a weight you choose to carry.”

I thought I was finished.

But the letter uncovered a paradox:

“At some point I realized that the ‘unhappiness-as-a-road-to-happiness’ approach had some problems: How would YOU reconcile YOUR OWN Es and Os without perspective, if YOU cannot have perspective, without first having had to reconcile YOUR OWN Es and Os? And how could YOU possibly ‘choose’ the weight YOU ‘want’ to carry? I was stuck, again.”

You need perspective to reconcile expectations with outcomes. You get perspective from reconciling expectations with outcomes. Which comes first? The circularity was irreconcilable because the loop requires what it produces.

The letter ended with a promise:

“GOOD NEWS FROM NIMBIN!

I believe I may have found answers to all these questions.

My General Theory of Reality will give you an understanding of how every environment works, and it serves as a guide for the amelioration of the human condition. (It also reconciles quantum physics with relativity using the Principle of Causation Incoherence.)

I’m coming home to share this with you.

Love,

/Dad.”

I had a method and a paradox. When you can’t define the what, work with the how. But it was the paradox that would drive me forward.

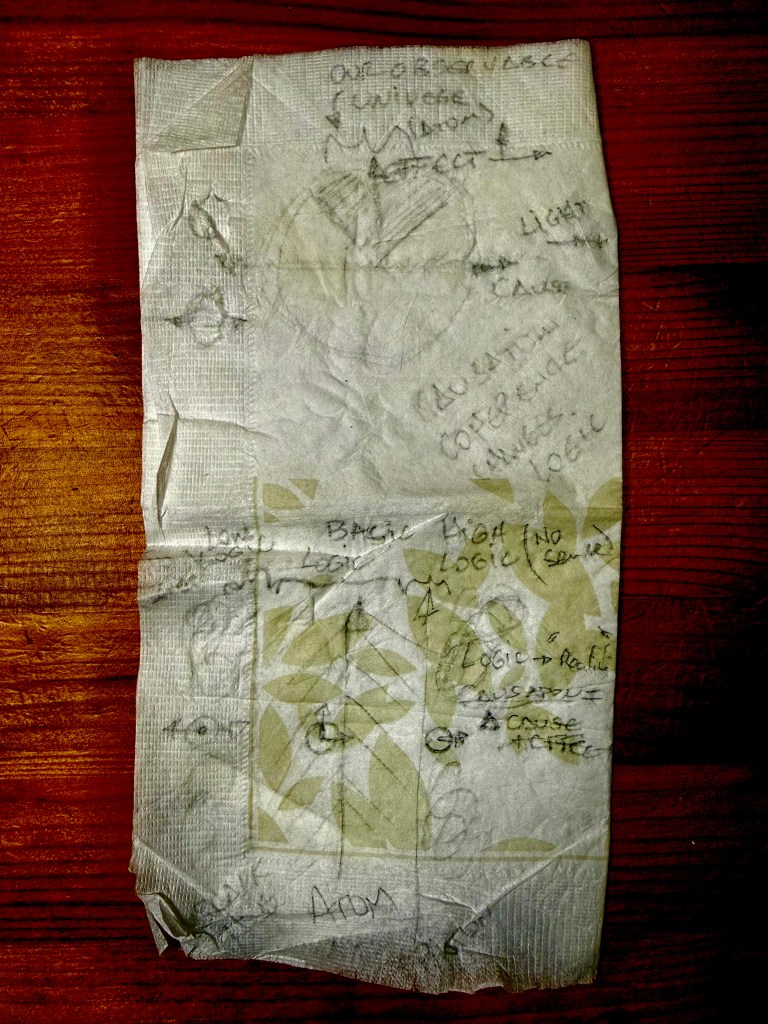

I also had a primitive concept of Incoherence. A month earlier, during a Continuing Legal Education class in Texas, I’d written on a napkin: “causation coherence changes logic.”

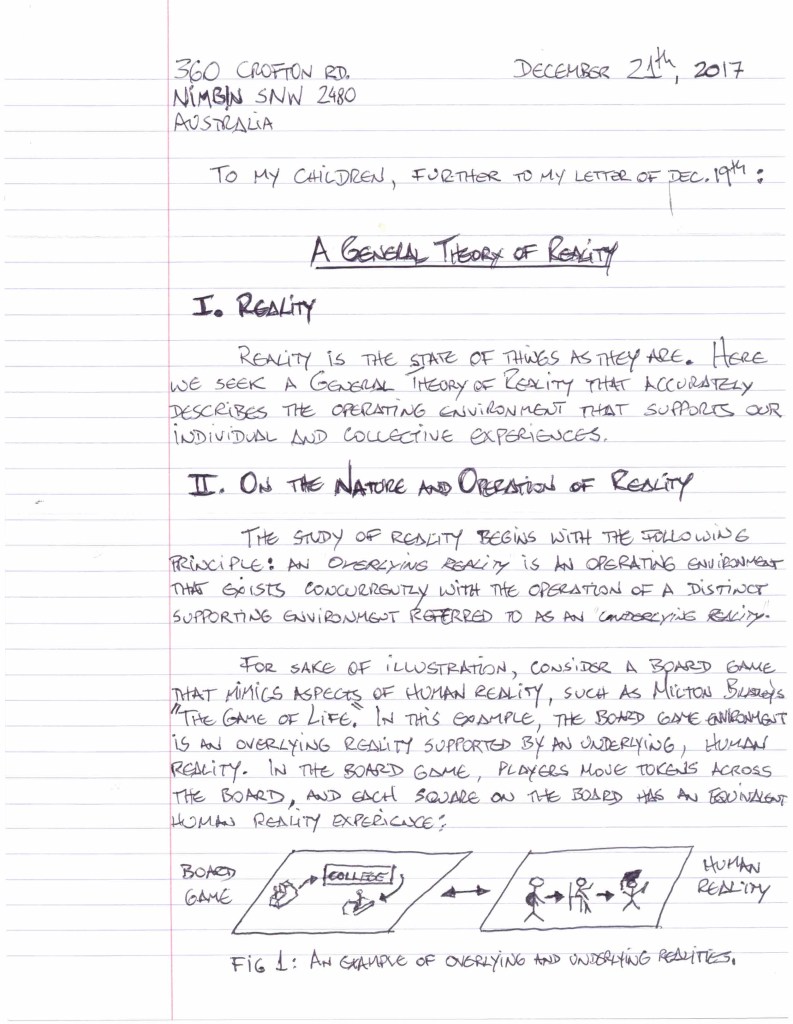

A False Start

I wasn’t versed in philosophy or science or religion. My whole life I worked with inventions, but nothing like this. I had instincts and the tools of a patent attorney.

This turned out to be an advantage.

It all started with a question: “Why doesn’t human experience match physical reality?”

The observation about physical and abstract layers of reality held up. The way I described how those layers connected through a “causation function” was mostly hand waving.

The board game “Game of Life” was a good illustration:

“In this example, the board game environment is an overlying reality supported by an underlying, human reality. In the board game reality, players move tokens across the board, and each square on the board has an equivalent human reality experience… The human experience of obtaining a college degree, for instance, is much richer than its counterpart board game experience: in human reality, the college experience may involve traveling to and from school every day, attending dozens of lectures, passing a number of examinations, and so on, for several years. In contrast, to get a college education in the board game, a player simply spins a wheel and moves a plastic token to the ‘college’ square.”

The suitcase example followed:

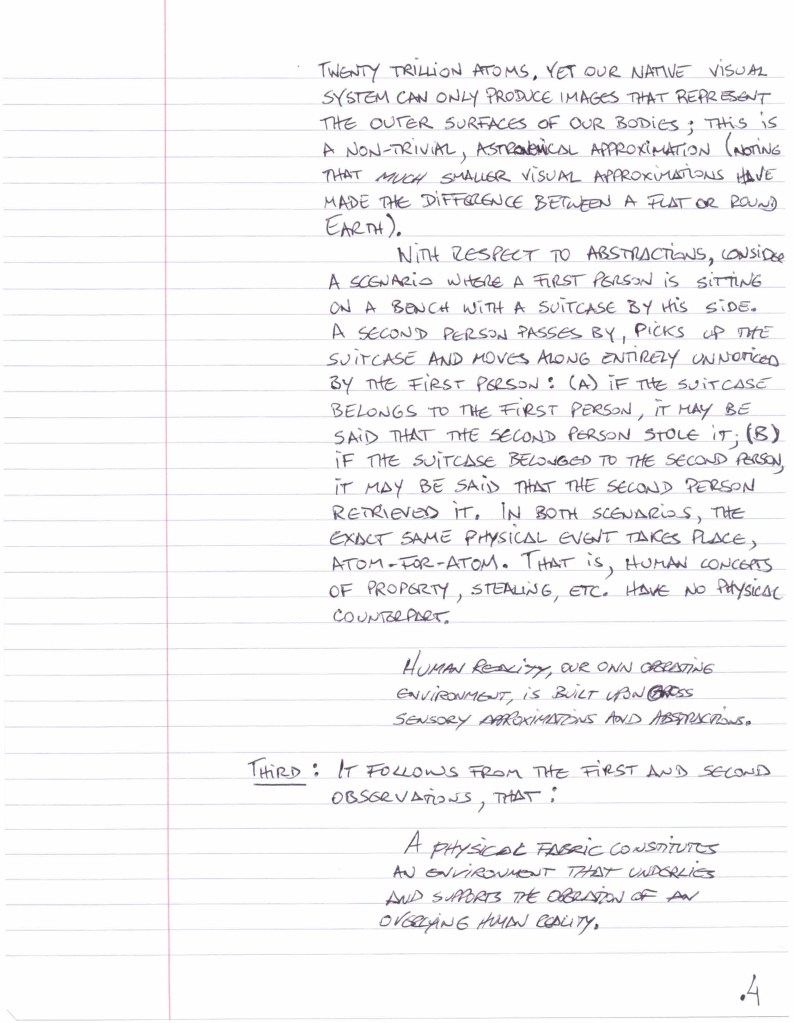

“With respect to abstractions, consider a scenario where a first person is sitting on a bench with a suitcase by his side. A second person passes by, picks up the suitcase and moves along entirely unnoticed by the first person: (A) if the suitcase belongs to the first person, it may be said that the second person stole it; (B) if the suitcase belonged to the second person all along, it may be said that the second person retrieved it. In both scenarios, the exact same physical event takes place, atom-for-atom. That is, human concepts of property, stealing, etc. have no physical counterpart.”

One conclusion was right:

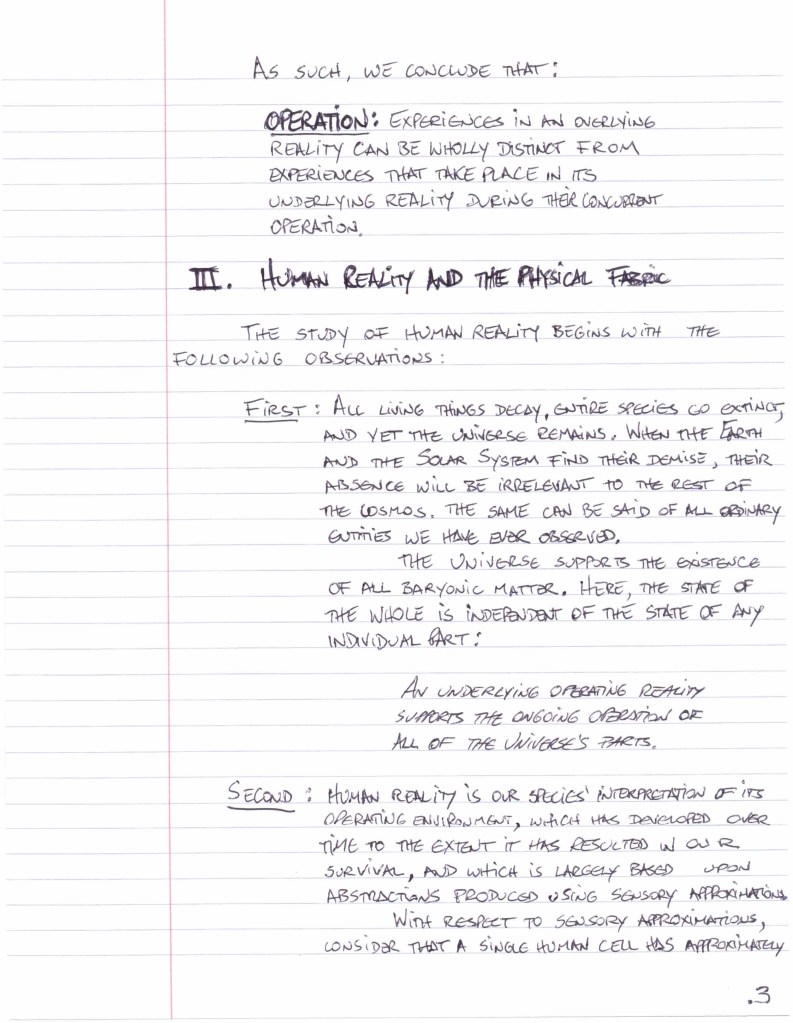

“Experiences in an overlying reality can be wholly distinct from experiences that take place in its underlying reality during their concurrent operation.”

In the board game, overlying was the game and underlying was the human reality supporting it. I was trying to show that two people could share an event without sharing what it meant.

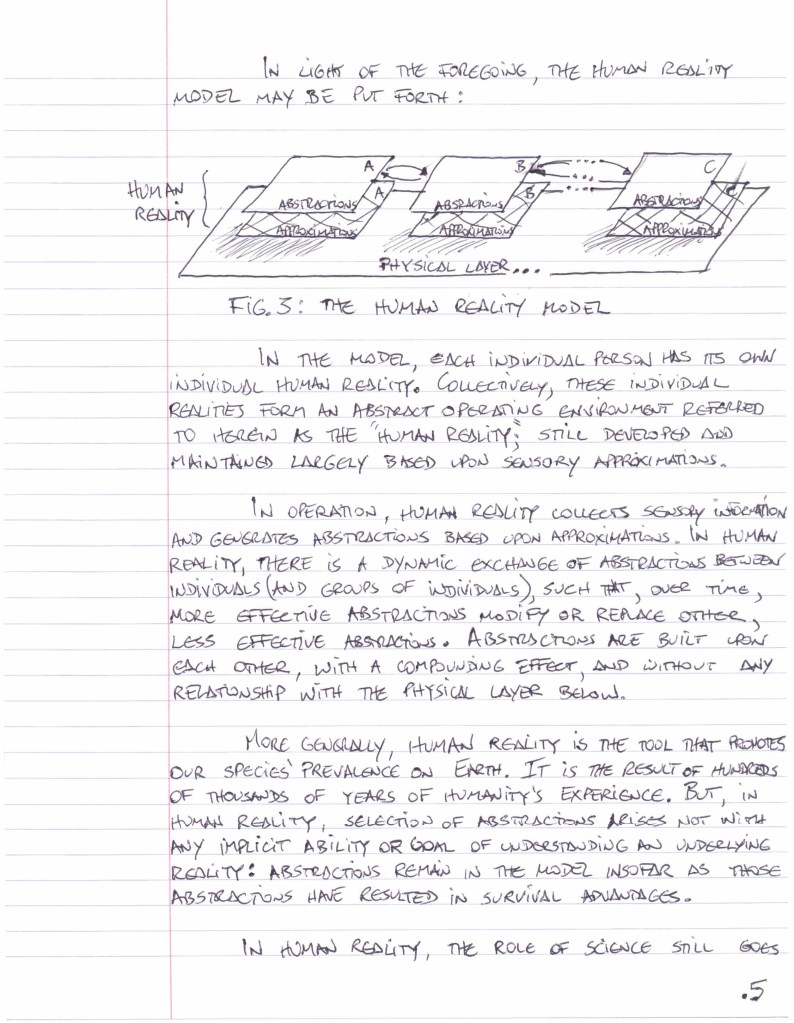

I tried to show the layering in a diagram with a physical layer at the bottom and individual human realities at the top. Between them, I needed a bridge. “Approximation” was a placeholder.

Orthogonality and parallelism weren’t visible yet. These were just layers stacked on top of each other.

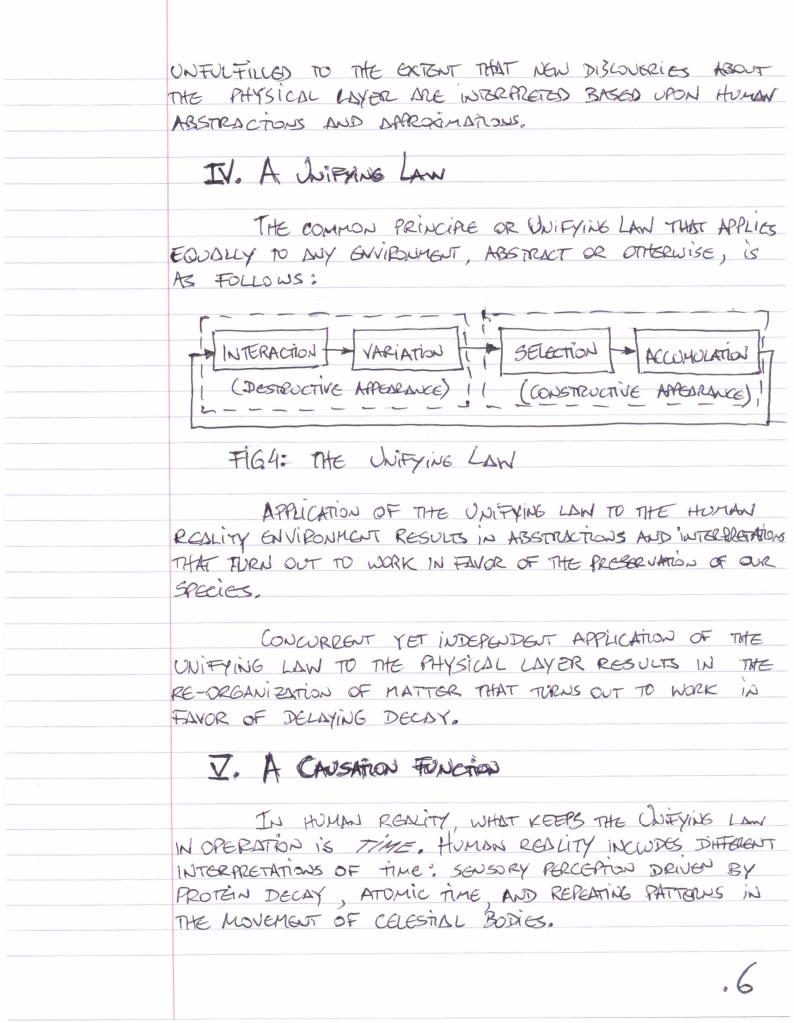

I added a “Unifying Law.” The figure showed interaction and variation feeding into selection and accumulation.

“Human reality collects sensory information and generates abstractions based upon approximations. In human reality, there is a dynamic exchange of abstractions between individuals (and groups of individuals), such that, over time, more effective abstractions modify or replace other, less effective abstractions.”

What it got right about abstractions replacing each other, it lost on meaning. The letter had people exchanging meaning directly, as if it could travel.

I was thinking about happening. In the board game, what links events is the spinning wheel. In human reality, what links experiences is time. In the physical layer, what links events is causation. Each context had its own mechanism.

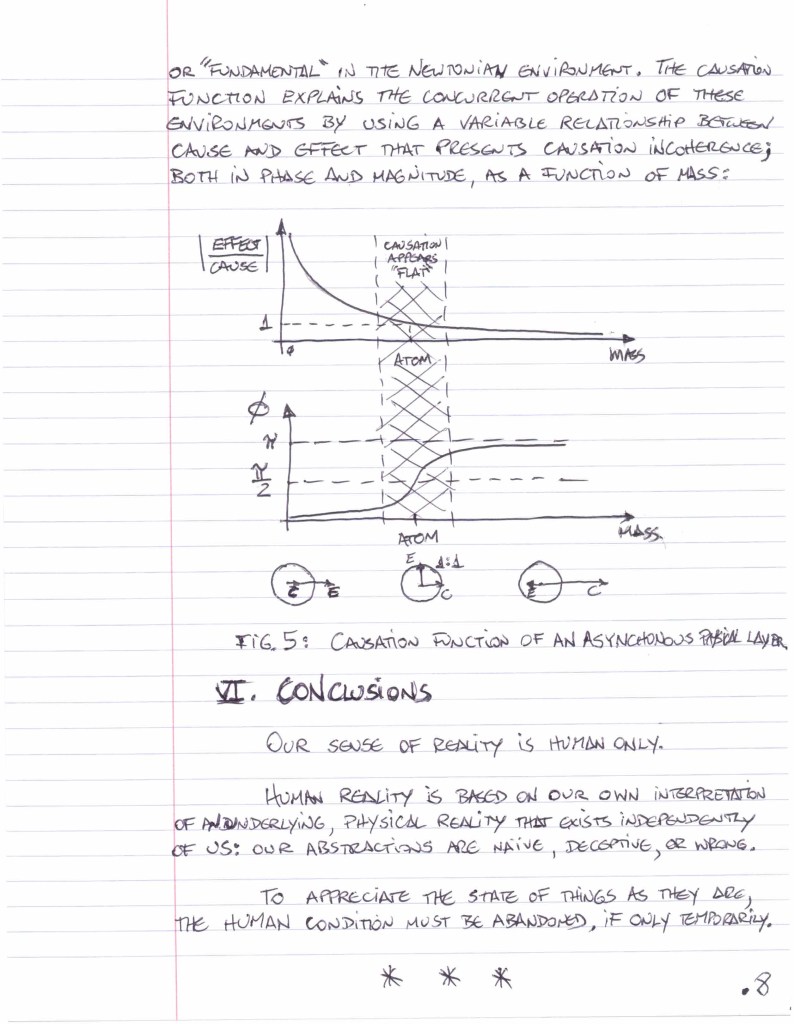

“More fundamentally, in the physical layer, a causation function appears linear or ‘flat’ as in the Earth is flat, or ‘fundamental’ in the Newtonian environment. The causation function explains the concurrent operation of these environments by using a variable relationship between cause and effect that presents causation incoherence; both in phase and magnitude, as a function of mass.”

Causation varying across scales was new ground. But I’d started from the physical world, atoms, mass, Newtonian mechanics, and that assumption guarantees failure. The physical world is an interpretation. It doesn’t contain happening.

The letter closed:

“Our sense of reality is human only. Human reality is based upon our own interpretation of an underlying, physical reality that exists independently of us; our abstractions are naïve, deceptive, or wrong. To appreciate the state of things as they are, the human condition must be abandoned, if only temporarily.”

I was looking for a perspective outside the human experience.

The letter posed good questions with no way to answer them. Every problem it identified became years of work. Much of it was wrong.

I knew the room was dark. I had no idea how dark.

One month later, I tried again with crayons.

Out Come the Crayons

I wrote “On the Human Condition” in March 2018. This was the third thing I’d sent the kids in four months, and it did something the earlier ones didn’t. It introduced color.

My youngest son had just turned two. The house was full of crayons.

Blue for Physical Fabric. Red for Human Reality. The visual distinction appeared months before these domains had names.

The paper opened:

“All matter shares a common Physical Fabric (PHY). Human Reality (HR), however, is abstract.”

I was still treating the physical world as fundamental.

The paper continued:

“Human beings experience a grossly simplified version of everything around us, including ourselves. To create an individual HRi, our biology uses sensory approximations and minimalist representations of PHY entities and processes.”

I was treating perception as a simplification of a physical outside. That assumption causes problems from the start.

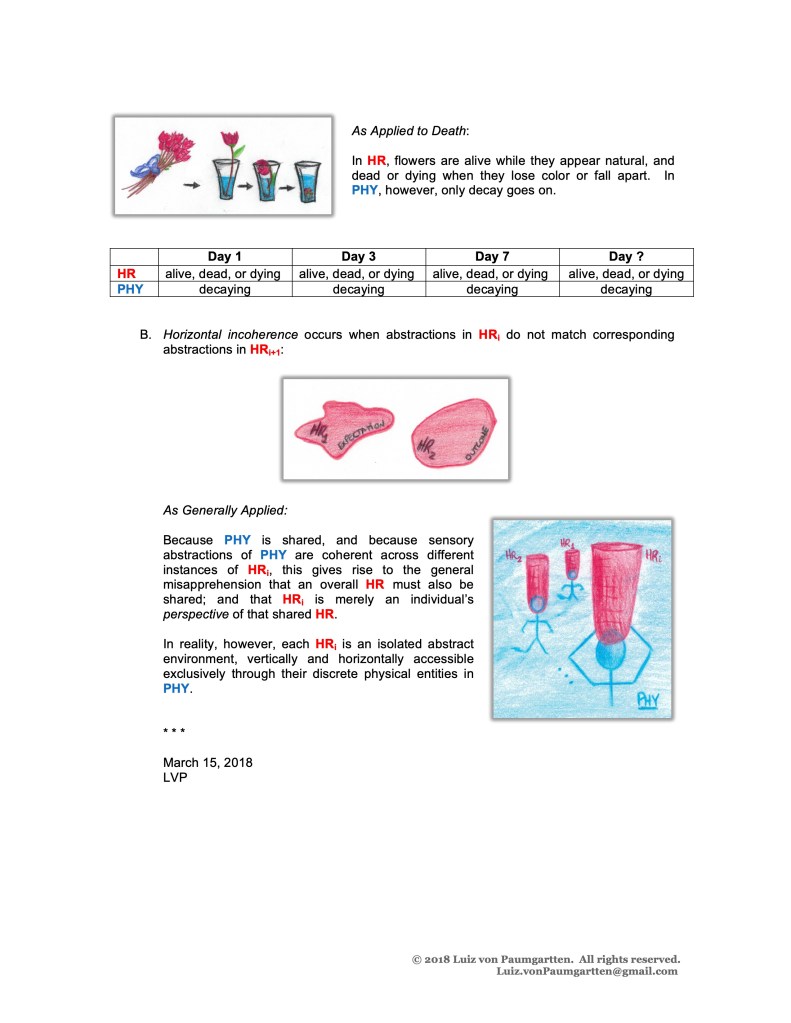

Incoherence appeared next:

“Vertical incoherence occurs due to approximations and weak dependencies between HR and PHY, such that abstractions in HR do not match corresponding physical entities and processes in PHY.”

Two examples:

Life: “Two already-living cells, a sperm and an egg, interact in space and time, performing a transformation of matter that results in a child. In HR, life begins here. In PHY, however, no new life is created.”

The cells interact and transform matter. In human reality, a new life is born. Same event, different meaning.

Death: “In HR, flowers are alive while they appear natural, and dead or dying when they lose color or fall apart. In PHY, however, only decay goes on.”

The mind marks transitions: alive, dead, dying. The process is continuous decay. The meaning changes at arbitrary points.

Dissonance came next, as “horizontal incoherence”:

“Horizontal incoherence occurs when abstractions in HRi do not match corresponding abstractions in HRi+1.”

Because PHY is shared, and because sensory signals respond to the same causation, people assume they must share HR too. That everyone’s interpretation is just a perspective on one shared world.

The paper pushed back:

“In reality, however, each HRi is an isolated abstract environment, vertically and horizontally accessible exclusively through their discrete physical entities in PHY.”

The mathematical notation was everywhere: HRi, PHY, HRi+1, Δ. This was an effort to pin down distinctions I could feel but couldn’t articulate. I thought there was a delta between HR and PHY, as if they were two different types of things.

Colors worked better than language. Crayons don’t pretend to explain themselves the way words do. They just show.

By the end of the paper, blue stick figures had their heads inside their respective Red Spaces. One of them was pushing it away from himself, creating distance, trying to separate himself from his own interpretations.

That stick figure was me.

Emergence of a First Principle

The kids were too young to understand what I was doing.

So I wrote them a story.

The Baroness commissioned a toy maker to build a model of the world for her son. The toy maker created it with puppets. The Baroness demanded the puppets be made to act like real people. The toy maker called in the Abstractionist, who made them function that way.

When Nimbin entered the model, he didn’t come back. The Baroness put on Opera Glasses the Abstractionist gave her. The model lit up blue. She found Nimbin comforting a weeping puppet trapped under a translucent red veil floating above his head.

The Abstractionist explained what he’d built into the model to make the puppets human. Two parallel layers. A shared Blue Space at the bottom where all things exist as they are. Individual Red Spaces above, one for each puppet, where each one lived in meaning they created alone.

Nimbin saw improvements everywhere in the Blue Space. Longer, safer, healthier, better lives. But the puppets in their red veils remained dissatisfied. That gap, that “incoherence,” was what made them human.

Nimbin gave the Opera Glasses to the weeping puppet and asked him to pass them on. The puppet who received them learned to see the Blue Space and became the Puppet King.

Nimbin and the Abstractionist raised every question but answered none.

How exactly do red and blue relate? What separates them? The Puppet King could see both, but the story never explained how. It just showed it.

After that, I started publishing explanations online. The Toy Maker’s Model and how it operated. The puppets and their red veils. The Opera Glasses and their purpose. What it meant to escape.

Everything was there in the story, but I had to extract it, expand it, explain it, and test it. A lab notebook was where I developed the thinking. The blog posts came from that.

The letters, the papers, the story, the notebook, the dozens of blog posts. It was all one process, one long engagement with a problem that wasn’t just about a fable anymore. It was about reality.

I eventually published a book called Principles of Natural Reality.

I hadn’t finished working out light as the boundary between red and blue. I took the book out of print and briefly gave up on the project.

But I couldn’t stay away. Thomas Edison knew how to build the bulb. He had all the pieces. What he needed was the one element that would glow without burning out.

What I needed was a proper boundary between meaning and happening, one that connected the two without collapsing them into each other.

Light found its place when I stopped trying to make Natural Reality a theory of everything and let it be a map. The approach came from my first letter: if you don’t know what something is, figure out how it works.

By then, I knew the map worked. Natural processes, each with an inside, an outside, and a boundary.

In 2024, I wrote The Intact and the Flightless. A bird born with giant wings, hiding from the Flightless who always clipped everybody’s wings. The Intact kept his and learned to fly. The yellow triangle at the center of the story represented his discoveries.

Wings are whatever trait or gift makes you who you are. Whatever you’re born with that the world wants to clip away. In my case, wings represented neurodivergence. The Napkin Sketch itself came from distraction.

I started expanding my blog posts into long form articles. For a full calendar year, every day at 3:00AM, I wrote. At some point I had enough to fill three or four books. I didn’t know which direction to go.

Glitches in Reality was my way of finding out. Eight years of work compressed into ten minutes. It proved the material could work as one piece. I organized the articles so the ideas explained themselves.

The Abstractionist’s Papers went live in February 2025.

I had delivered Natural Reality. But revisions continued for ten months after publication. Some based on feedback, others on my own realizations.

When the editing slowed, I went back to Glitches.

The second time through, with everything I’d learned from writing The Papers, I tore it apart and rebuilt it. All complication fell away.

Meaning and happening arose as everyday words where I’d needed technical language before. So I returned to The Papers and reworked a few chapters.

And that was it. The pass thrown in 2017 was caught.

Whether anyone cares is another matter.

That meaning and happening are orthogonal makes Natural Reality a multigenerational project. Euler worked with imaginary numbers in the 1700s, the square root of minus one, something you cannot see or touch. It took Legendre and Chebyshev and mathematicians the entire nineteenth century to accept it.

That’s why I still work on this project now that my children are grown: oneness and otherness.

The Problem with Materialism

I spent the entire first year of this project treating the physical world as the place where happening occurs. That was the mistake. When the physical world contains happening, interpretation and causation collapse into each other. You lose the distinction between what happens and what it means.

This is a category error. You never perceive happening. You build meaning from signals that reach you. When you think you’re perceiving happening through the physical world, you project your own inside upon an imagined outside. Collapse the two and the dimension where causation runs is gone.

Materialism works well enough at close range. You see wet pavement and assume rain. A fever breaks and you know the infection is responding. It’s so effective at the short scale that you never feel the cost of missing anything.

Yet the cost is real and personal.

Without the distinction between meaning and happening, you can’t see the parallelism between minds. You think you’re dealing with other people, but you’ve only ever been handling your own interpretations of them. Who they are stays out of reach. There’s no boundary you can locate, no place where one mind ends and another begins.

You can live your entire life unable to see that every mind around you is in the same condition. And you miss your own participation in the one happening all minds share, where your influence continues.

That’s where loneliness lives.

Why You Don’t Go Back

Every morning you wake up and plug in. The world arrives ready-made. What things mean, what people intended, what just happened and why. It feels like the outside coming in. That’s how minds work.

Most of the time it works well enough. But there are gaps that don’t close. You learn to live with them. Everybody does.

Then you find the map.

The first thing it shows you is that the world you felt excluded from was never a real place anyone else was living in either. Every mind is doing what yours is doing, producing its own reality, responding to the same happening in its own way, with no more access to the outside than you have. The loneliness that came from feeling like you couldn’t reach something eases when you understand there was nowhere to get to. What you share with every other mind is the happening underneath, one causation moving through all of you. Your influence enters it and travels past any single conversation or lifetime. You feel oneness in a new way, and that feeling grows. Your game gets longer.

The second thing the map shows you is where everybody else is. All you have ever had of another person is your own interpretation of them. This understanding of otherness changes how you deal with everyone. You slow down. You become more curious. You stop being yanked around by every signal that reaches you. You make room for others. It all follows naturally from knowing the boundary.

The third thing is harder to summarize because it’s the entire map. You can see your own loops: how your interpretations trigger responses, how those responses confirm what you already believed, how the whole thing feeds itself. You understand what paradoxes are for and what to do when one appears. You see how influence propagates and how emergence works. Agency becomes a practice.

The old way had none of this.

The Eddy Network

Ed Brenegar invited me on his podcast.

I had three months before the recording, so I asked my oldest son if he’d help me practice. We did several conversations about Natural Reality together.

On December 5, 2025, Ed and I recorded without a script and just improvised. I told him at the start: “This is my one podcast book tour.”

The Eddy Network podcast focuses on global conversations with local leaders exploring how people think about leadership and the work they do in their communities.

Here are some excerpts; the full episode is available on YouTube.

Ed opened by describing what concerned him.

Ed: “We live in a time of unreality and disconnection from reality. I find that people trapped in simulation or false reality. It does not make their lives better. It does not elevate their agency as persons. It does not make their relationships more respectful or trusting. A large number of the problems that we face today in the world are because we accept a false reality that we choose because it actually relieves us of responsibility.”

He was right. And the solution is a map.

Me: “I agree with you. We’re left with the question of how do we address the problem of getting lost in our own worlds of make-believe. The proposed solution is a map.”

Me: “We’re talking about reality, but we could be talking about different things. The Abstractionist Papers deal with reality differently than philosophy, science, or religion. It’s a map. Not a theory of where we came from or where the universe is going. It doesn’t answer those bigger questions about what things are. Instead it goes into the world of how, which is how reality works. It’s very practical. Its primary use in daily life is to live better day-to-day with other people, other processes emerging just as you are.”

Ed: “I know exactly what you’re saying. Well, exactly is the wrong word. I do understand what you’re trying to say.”

Me: “That’s why I say at the end of the book, this is the largest abstractionist job I’ve ever attempted. You have to find the relationships that give rise to the forms that we see.”

Ed nodded and pulled out a sheet of paper.

Ed: “I’m looking at some of it. I printed off some of this this morning because there was one piece that I wanted to read. This is part of a letter from the abstractionist. It all began with a simple need to understand how we navigate a universe. We live inside but never see directly. As a child in Brazil, I watched our fish in the glass of their bowl, wondering what they thought about the world moving beyond. To them, everything must have seemed contained in that small space. They had no idea anything was happening outside. Years later, I recognized this as my childhood version of Plato’s cave. We all start with one way of seeing. Learning to see differently takes effort. Picasso created 11 lithographs of the same bull, each one simpler than the last. He kept removing details until just a few essential lines remain. And somehow that captured the bull more truly than the realistic version. Abstractionism strips away what obscures until what matters stands alone.”

He paused and reflected on it.

Ed: “I thought that was really well said and it makes the idea of something that’s being abstracted worth looking at because I think that abstractions have become tools for denying reality. And what you’re trying to say, I believe, is you’re trying to create a sense of an appreciation for these abstractions as a way of revealing what reality is. Am I correct in that?”

Me: “It’s an interesting way to try to make sense of things without knowing what they are. Reality is relative, relational. Learning a little bit about relationships and how they work, which is an abstract world, pays off big time.”

Earlier I’d tried signal processing as an analogy for Red Space and Blue Space. Too technical.

But we moved on. I said:

Me: “Each one of us has our own version of reality we produce inside. And to each of us, that reality being produced inside feels like it’s the outside. In other words, we’re living our inside lives outside. Without being aware of it, at least not fully aware.”

Me: “Nowadays it’s difficult for me to imagine really being able to appreciate and account for another person’s presence unless I had the boundaries drawn in this way where meaning doesn’t transfer between us. If you don’t draw the boundary in this way then you have the possibility of meaning transferring between us but that never happens. Meaning always stays inside. And so that distinction is basic for appreciating other minds and allowing them to be, or sometimes containing them. It depends on the situation. But just at a human level, to be able to appreciate and account for each other, to account for otherness, that’s something.”

Ed moved to the practical challenge:

Ed: “So you and I are having this conversation and you have a reality and I have a reality that is our own unique reality and it operates within ourselves and the challenge is how do we come and communicate with one another? How do we share?”

Me: “You can produce some happening that becomes the expression of that idea. It’s not the idea itself. The idea is cards that only you can see. They see the other side of the cards. They see some expression. That expression is of a different nature than what you’re producing. It gets interpreted by them in their inside, in their own way. You have absolutely no real control over how signals get interpreted by somebody else.”

I put the obvious objection on the table:

Me: “So if meaning doesn’t transfer, then what’s the point of anything? Well, that’s a legitimate initial reaction. But once you have a little bit of time to sit with it, you realize how magical everything really is. Because to me, my present experience right now is that you’re on my screen in front of me. I know you’re somewhere else. The real connection comes from knowing that disconnect exists but we’re still here, building things together. That’s just magical.”

Ed: “I agree with that.”

Me: “The human condition is the number one cause of human problems. Being able to see a map of how it builds up, how it accumulates, so that you have a shot at sitting on a different chair from time to time, observe your reactions, your feelings from a different place and manage it in a different way, more deliberately, that becomes a practice.”

Then Ed said something about his own mind. He felt like it wasn’t big enough for him. I came back to it.

Me: “I love what you said earlier about your mind not being big enough for you. I love the way you said that. I’ve never heard it said like that. It’s kind of like ‘this town’s not big enough for me.’”

I saw an opening. If a mind is not big enough for you, that’s because you’re always in a potential and flow relationship with the rest of the process universe.

Me: “You know, potential and flow are ways to describe what we think about as energy. It’s what makes things go. You can be charging a battery, accumulating potential. Or you could be reading a book, accumulating potential. And then eventually that potential turns into flow. Either because you flip the switch and turn the circuit on, now drawing current from the battery. Or because you read an amazing book and now you brought extra flowers for your wife, whatever it is.”

I couldn’t quite show the connection, but Ed was gracious and we moved on.

Near the end, Ed mentioned The Abstractionist’s Toolkit.

Me: “I had this nagging idea that what we were doing at our desks wasn’t really engineering or law or patents or inventions. It was about developing quick ways of seeing things, making sense of them, to be able to then do your job with them because everybody will know if you don’t, you know, like you can’t hide the text you end up writing at the end. I always had this feeling that there was more to it, but I didn’t know how to articulate it at the time. And then several months after the book was published, I thought, why not? I might as well fit that in while I can, right? And so that’s how it got there.”

Ed: “Which I found very helpful.”

When we were done recording, Ed mentioned Mark McGrath to me. Mark taught John Boyd’s work, and Ed thought we should connect.

I reached out.

No Way Out

Mark McGrath teaches John Boyd’s OODA loop. Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. It describes how living systems read uncertainty and make decisions. It’s essential to strategy, cognition, and how organizations adapt.

When we talked, Mark was working through a teaching problem. Most people looked at the OODA loop and saw sequential steps. They treated it like a template, one phase after another, and couldn’t generate novelty that way. When orientation got attention at all, its depth got overlooked. Mark was trying to show them that orientation is the engine. It determines observation, decision, action.

I recognized both problems. I’d been working through the same ones.

After an initial conversation, Mark invited me to his podcast, No Way Out, with his co-host Brian Rivera, also available on YouTube. They examine the OODA loop across different domains and disciplines.

I said yes. I had ways of showing things that might help, and they were exactly the kind of experts I needed to stress test Natural Reality against.

I came in with two goals: show the distinction between meaning and happening, then show how orientation emerges.

I started with a red sheet of paper.

Me: “Meaning, what is meaning? How am I defining meaning? Meaning is everything that the mind produces. Every thought, every visual image that you perceive, every sound that you hear, absolutely everything. Your understanding of what I’m saying, your feeling of sitting on a chair or standing. All of this stuff belongs to meaning, to the category of meaning.”

Then I held up the blue sheet.

Me: “And then on the other side, you have the world of happening. Happening is what occurs. One way to think about happening is actions, interactions, responses, behaviors. But the truth is, as soon as we start naming the happening, measuring the happening, we’re no longer dealing with the happening. We’re dealing with meaning again.”

I made the papers perpendicular to each other.

Me: “Meaning connects to happening and happening connects to meaning through something that we’re used to calling light. Light is the boundary between meaning and happening. Let me take a moment to make sure this makes sense. When I look at my cup of coffee, there’s light that hits this thing and then reaches my eye. In response to that light, my nervous system from the eye all the way to eventually lands on my mind, on the inside. That light gets interpreted as an image. Sound works the same way. You have pressure waves reaching your eardrum, and then it’s light. It’s electrical. The nervous system is electrical. So it’s light that flows from the eardrum all the way to eventually becoming sound in the mind. And on the way out, how do we connect from the inside towards the outside? It’s also through light.”

Mark was nodding. Brian was watching.

Brian walked through active inference and the free energy principle, connecting what I was describing to their work.

Me: “Let me ask you something. This is just natural world stuff. If I play some music, whatever music it is, and then you dance. Did the music make you dance? Or did you dance in response to the music?”

Mark interrupted. He had a story.

Mark: “Oh, that wouldn’t hit me because it actually happened to me last night. I was taking the recycleables out, which is otherwise tedious, and I put on the song, New Age Girl by Dead Eye Dick from the 90s, and I just start jiving and it makes the thing. When you asked me, I really started to think, wow, that just happened to me. What was it?”

Me: “So did the music cause you to dance?”

Mark: “If you don’t want to dance, you’re not going to dance. Sometimes you’re not paying attention to it. But nothing from the outside like that can make you do anything. You’re doing it in response to it.”

Me: “Right. Nothing from the outside causes you to do anything. You respond to signals. Your mind responds to a signal. The only thing that the signal brings is a variation that we then interpret as something, but the signal itself is just the way we model it. It’s up and down variation. It doesn’t carry any meaning. For example, when you see an image of something, the image doesn’t come in through the light into your eyes. Light gets to your eyes and then you produce that image inside.”

Brian: “Exactly. We would call that perception. And then Boyd wrote it down as implicit guidance and control that goes from orientation to observation. It’s a negative feedback loop, which actually acts as a filter.”

Me: “That’s one of the things we get trained in. We’re always figuring out causality in a different way. It’s not enough to see the sequence and say what came after was caused by what came before. Because you do have a lot of responsive behavior. That’s how nature works. It accepts responsive behavior. When some signal reaches the entity, the entity inside produces its own interpretation in response to the signal. But nothing from the signal itself determines this. The only thing that the signal brings is a variation.”

Me: “Imagine you’re young and you learn a rule. Everything that goes up must come down. You see apples falling from trees. You see things jump and fall back down. That reasoning always works for you until one day you look up at the sun and realize: the sun’s been there since yesterday. The sun’s not falling. What’s going on?”

Brian: “That’s a paradox.”

Me: “That’s a paradox. I wonder if they can’t reconcile: how come the sun is up in the sky if everything that goes up must come down? That’s just the world they have inside. It’s a simple rule. It’s not what we know to be gravity today, but we all have to start somewhere and that’s the reasoning they have. What this diagram in Chapter 4 shows is the Causation Domain, or Blue Space. This world of happening. You have that circle number 1, and what that represents is a happening where the sun is up in the sky. Number 2, still in the Blue Space, is another happening, a subsequent happening where the sun is still up in the sky. So how does our person, our observer, see any of this? They see from inside their minds. Up until now, blue and red are perfectly fine. You have the sun at item one and you have the meaning of the sun at A. But the person’s mind applies the reasoning: if the sun’s up there, it should be coming down, which leads to C. C is the idea that the sun shouldn’t be there, it should have come down. But what they see when they look up at the sky is something else. Their interpretation of event number 2 is not that the sun fell. B is that the sun is still up in the sky. They expect C because of their reasoning, but what they see is B, and in that gap lives the paradox.”

The territory operates in an entirely different domain than the map. They’re not approximations of each other. One is meaning, one is happening.

Me: “So why do people look at the OODA loop, for example, and their takeaway is sequentiality? The idea is they’re looking at a map, which is a map of meaning that’s representative of some happening. It’s good for us to understand the happening, but the map itself is obviously the map-territory distinction, right? The map’s not the territory. But what people have been missing, and what I try to add to this discussion, is that of course everybody has talked about map and territory before. But usually we look at a map as an approximation of the territory, a simplification of the territory, a limited version of the territory. What this work says is that the territory is of a different nature than the map altogether. The map is paper with symbols, and the territory is dirt, trees, roads. They’re not just different things. They’re different types of things. When you confuse the two, like we usually do, you look at the inside of your mind and imagine it’s outside. You expect your interpretation to be the happening itself. That’s confusing meaning with perception of causation. And that’s where the map-territory gets funky.”

Me: “You guys are very technical, so you will understand this right away. If you think about signal propagation, if you look at a waveform propagating in time. The analogy would be let’s look at the waveform propagating in time as if it were happening. Okay, it’s obviously not. It’s our model of happening, but let’s just say it’s happening for the analogy. Then we are looking at something that we usually call the time domain. We’re looking at how the wave propagates in time. But how do we find out what’s inside the wave? We apply a transform, a Fourier transform. And next thing I know, we’re in a different place called the frequency domain. Now we have the whole spectrum of the signal, the frequency content. The inside and the outside are connected by a transform and they’re orthogonal domains. That same principle applies here. The inside being meaning, what’s in the mind, and the outside being happening, the Blue Space. It’s not a perfect analogy, but it kind of gives you the idea of two orthogonal domains operating concurrently, with things existing in both domains concurrently.”

Brian: “That’s exactly what you’re describing here. Red Space and Blue Space are orthogonal domains.”

Me: “Everything in red is meaning. Everything in blue is happening. They’re connected by light, which is the transformation between them. And the critical part is that they operate by different rules. You can’t access blue from inside red. You can only respond to signals from blue that reach the boundary and produce meaning inside red.”

Me: “Now, this orthogonal idea applies everywhere, even to information. We split information into two sides: the meaning side and the variation side. When you get a signal, air pressure waves are progressing toward you. There’s no meaning in that, no sound. Just variation. You produce the sound, you produce your understanding of it. When you get a light signal going up and down, your internal model interprets that variation as meaning. If it goes up twice, you interpret that as the letter A. That’s the meaning you attribute to it. Without knowing how to interpret a signal, it means nothing to you.”

The concept of two separate domains isn’t new. Eastern philosophy has been pointing at it for thousands of years.

Me: “The only thing I know about the Tao, I read a book about Winnie the Pooh. The Tao of Winnie the Pooh. What a fantastic book. And that’s all I know about the Tao.”

Me: “We don’t claim to be modeling the happening ever. Until we decide to, and then on purpose, we wrangle it with minimal interpretation. We do that in Part III of the book, but that’s very contained on purpose. We’re trying to make it useful. So we have to add meaning to be able to handle it. But outside of that, the Blue Space is not a space that we see or we deal with. It’s just like in the Tao.”

Mark: “I got holy spirit chills.”

Orthogonality is what makes the impossible possible.

Me: “I’m not a historian. This is just my version of the story. My life is fifth grade math, that’s what I do. But Euler was a genius, and his genius was recognized because his solutions dealt with orthogonality. At some point mathematicians couldn’t find the square root of a negative number. It’s not in the world of real numbers. What Euler did was create another dimension. He saw a different domain, called that an imaginary domain, and started working with it. He created a real plane and an imaginary plane and said the square root of negative one is what we’ll call the letter ‘I’, an imaginary number. And he solved so many problems that way.”

Wave-particle duality followed. The diagrams did the work.

Brian: “I’m going to say this in the rudest way I can. A patent attorney came up with this shit, okay?”

Mark: “Well, it looks like he was an electrical engineer or something like that.”

Me: “I can address that at the end, but that’s exactly what we are. We’re all engineers before going to law school and we still think like that after law school.”

Brian: “My mind, just standing here, I would think that my skin separates me from the external world, right? Because that’s what it kind of looks like. Somebody else may say, hey, I’m actually part of this world, the boundary’s further out than me, and that’s the extent of my mind, where the enacted part of this is.”

Me: “In Natural Reality it’s different. The skin is not the boundary of you. It’s in the happening, so the Blue Space. In natural reality, the Blue Space is one. There’s one world of happening and there are no divisions. There’s no meaning, so we can’t separate. We can’t sit here and start labeling things and separating things. There’s no meaning in the world of happening.”

Me: “What we call the body is the mind’s interpretation of the processes, the happening that gives rise to it. When you walk around and see all the bodies in the world, you’re not seeing the bodies directly. You’re seeing your own interpretation of the happening that gives rise to somebody else’s mind, which you never actually get to see. Because the world of meaning is not shared. Everybody has their own individual mind. It’s a distributed reality.”

The first goal was done. Meaning and happening were distinct. Now came the harder one.

Me: “Imagine you’re eight years old and you set up a lemonade stand with a friend. And the agreement that you have with your friend is we’re going to do a fifty-fifty split of the profits. You set it up and make some money. On the day you’re supposed to set up the stand, your friend doesn’t show up. So it’s just you there working all day. At the end of the workday, your friend shows up and says, where’s my fifty percent? And you give it to them. Why? Because up until that age, you’ve been taught and you’ve learned that fairness is a fifty-fifty split if there are two people.”

Mark: “That’s the rule.”

Me: “Next week, same thing. Your friend doesn’t show up, wants their half. You give it. Week after that, same thing again. And at some point you realize that fairness isn’t fifty-fifty when one person didn’t work. It’s proportional. Equity.”

Brian: “Your perspective reorganizes.”

Me: “Here’s what happened: it’s cheaper in an economic sense here for the mind to readjust what it thinks fairness is than to carry those gaps along. You don’t want to keep paying the guy fifty percent. So you naturally learn to see it in a different way. Your resistance to the rule that says fifty-fifty is right increases. You don’t apply that rule the same way anymore. The rule that used to say fifty-fifty effectively becomes something else because it was cheaper at some point to restructure your idea of fairness. That’s emergence. That’s how orientation reorganizes.”

Me: “This is what we call Incoherence. It’s a change in your impedance, your resistance to the application of the rule. Remember the lemonade example where you have that fifty-fifty rule that’s causing you a lot of problems? Eventually that rule transforms into a different rule. And what we call that change in the rule application, which effectively creates a different rule. When you look at the hard problem of change, that’s where novelty comes from. It invariably comes from some process that figured out a different relationship to some rules that weren’t there before. Imagine the loop we’ve been discussing as sitting on a plane. You can move around that plane, make small adjustments, fight decay directly on the same level. But when the cost of carrying the paradoxes inside gets too high, something different happens. You move orthogonally to that plane. You pop off in a different direction. Your relationship to the rule changes. Your impedance to that rule increases. The rule that used to work for you effectively becomes something else. That’s when novelty appears. It’s not from making things better on the same plane. It’s from changing your relationship to the rules themselves when the pressure builds enough. That’s emergence.”

Brian: “One of the things that comes to mind when thinking about all this is yin and yang, and Boyd’s idea that if you’re waiting for equilibrium, you’re dead.”

Me: “Equilibrium is our idea of stability, but it’s not real in the world of happening. When you’re driving a car with a steering wheel in front of you, if you want to go straight, the last thing you’re going to do is set it straight and keep it there. You’re going to have to go to the left, you’re going to have to go to the right. There’s no other way to go straight. You’re always adjusting from side to side. And on average, if you look at it for a number of iterations, you might call that stability. But ultimately, the only way to really move forward is to go side to side. And we see that everywhere. The only way to move forward is through that constant adjustment. That’s not a decision. That’s not linear. That’s just how minds work.”

Me: “In the world of happening, General Selection isn’t four steps happening in sequence. They’re all happening at once. And when you think about what the happening is, it’s just one. It’s the interaction. Step 2, variability, is our interpretation of a consequence of the interaction. Three, which is selection, is just an effect in the presence of decay. Whatever decays more will last longer, so we have that selection effect. It’s an interpretation again. And number four, the accumulation. We’re just making an observation in our world that these things accumulate. So when you think about the meat of this, it’s really just one step. It’s just the interaction. Everything else is sense making that helps us understand what might be outside, but it’s not what’s going on outside. And I think that ties very well in some ways to the idea that orientation really is everything.”

Me: “When we look at the general selection loop from the top of these stacked boxes, which is our natural way of seeing things, we see a loop that doesn’t really go anywhere. To really see where novelty comes from, where new rules appear and people start behaving differently, you have to account for a world we don’t usually seem to care about, which is the world of happening. You have to almost see it sideways. You can’t see it from the top. When I had the piece of paper, that’s the flat loop in front of me. The rest of the loop you’re talking about, the reason I don’t see it is because it’s like this behind it. It’s the causation axis. It goes in a different direction.”

Meaning and happening were distinct. Orientation reorganizes through accumulated Incoherence. Both points were made.

They’d been working the same problems from a different direction.

Me: “I worked on this project for a long time. And the whole time it was just inside. I wasn’t really trying to meet people to talk about these things. It was nice to come out here and discover that there are other people on similar journeys doing the same sorts of things. It’s a beautiful way to share.”

Mark: “We’re going to have to pause because this is clearly the first of several more discussions around this.”

Two hours wasn’t enough.

Natural Reality works.

Conclusion

In Nimbin and The Abstractionist, I created a character with ideas I barely understood. In The Intact and the Flightless, an odd bird returned with the yellow triangle.

Between the two stories: eight years of Natural Reality.

When I went on No Way Out, I was doing what the Abstractionist and the Intact did. Those characters walked out of the stories and into real life.

The same day the episode went live, a military teacher from Sweden reached out. He’d watched the show and recognized how to add Incoherence to Boyd’s OODA loop. He’d drawn Red and Blue Spaces onto his own sketches and shared a few of them with me.

With this, the spiral completed one revolution.

Emergence is the only show in town.

Epilogue: Abstraction Under Pressure

Let’s go back to the beginning.

When Brian Rivera asked, “A patent attorney came up with this shit?”, I decided to answer it by writing The Only Show in Town.

But the real question is why a patent attorney specifically.

In patent prosecution, abstraction is all you do.

Every day you strip an invention of its accidental form. You separate what it does from how it happens to be built. You identify what persists across different embodiments. You hold multiple perspectives simultaneously: inventor’s vision, examiner’s skepticism, competitor’s workarounds, litigation.

You draw boundaries that must survive sustained attack.

By the time I went on No Way Out, I had been doing this every day for over twenty-four years. A map of reality could only come from here.

Appendix A:

The (Un)Happiness Letter

Appendix B:

A General Theory of Reality

Appendix C:

On the Human Condition